As early as the Muromachi period, tea and tea utensils were introduced from China to Japan. At that time, tea rice was simple in ingredients and saved time for commoners who often did physical labor, and adding tea also had the effect of refreshing and invigorating the mind.

In "Konjaku Monogatari" and "Uji Shūi Monogatari," there are stories about the noble Sanjō no Chūnagon and tea rice and water rice. The chūnagon, troubled by obesity, sought medical advice and found a way to lose weight by eating tea rice (water rice) to limit his food intake, but because tea rice was too delicious, he ended up eating more and became even fatter.

During the Sengoku period, tea rice was referred to as "the food of samurai." In military campaigns, hot tea was poured over rice with seasonings, allowing for quick consumption to satisfy hunger and refresh the mind in the shortest time possible.

By the Edo period, tea rice became popular and its varieties became richer, while shops providing simple meals called "Chazukeya" also appeared, becoming typical fast food places for the common people.

After World War II, due to food shortages in Japan, many people relied on miso soup and tea rice to stave off hunger, which led to tea rice being regarded as a representative dish of the common people.

To this day, there are many varieties of tea rice, with increasingly refined ingredients and higher nutritional value. Adding wasabi, soy sauce, broth, mirin, and sesame to tea rice, along with various side dishes like pickled plum, seaweed, salmon, eel, cod roe, tuna, and sea bream, gives the originally simple tea rice infinite possibilities.

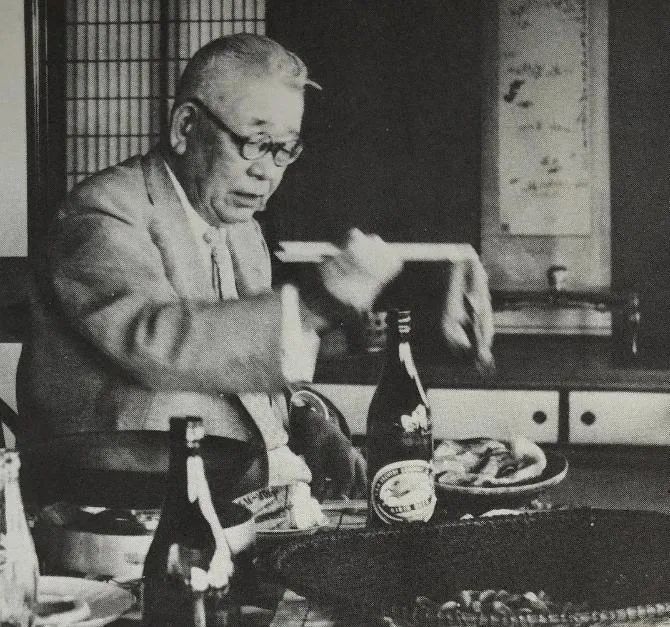

Kitaōji Rosanjin, known for his pottery and gourmet expertise, was very particular about the quality and taste of ingredients and utensils, making him a true connoisseur. He founded a membership-based restaurant called "Gourmet Club" and "Hoshikawa Charyo," creating a culinary trend of his time. This "person who has eaten all over the world," a true gourmet, was fascinated by the delicacy of Japanese cuisine and, after tasting countless delicacies, still had a special fondness for tea rice. He said, "After a hearty meal, sometimes I suddenly crave tea rice, and that desire just won't go away."

He wrote seven or eight articles about tea rice, introducing various types, including Kyoto's ayu tea rice, natto tea rice, and seaweed tea rice.

In his introduction to tuna tea rice, he wrote: "Add half a bowl of rice, then lay three slices of fresh tuna sashimi on top, drizzle with an appropriate amount of soy sauce, and place a small mound of grated daikon next to the tuna slices. Pour hot water slowly over the tuna from the side, through a tea strainer filled with tea leaves, evenly soaking the tuna with tea until the rice is completely submerged in the transparent tea water, and the tuna is also soaked in the tea."

Then, use chopsticks to gently press the tuna into the rice, and the still-red back will turn white. The transparent tea water becomes milky white, and after mixing in the soy sauce, the tea water becomes cloudy, with the fish oil floating to the surface. Mix the grated daikon evenly, and finally add a bit of wasabi, and the original aroma of the tea rice fills the bowl.

For salted trout tea rice, he also expressed: "Salted salmon should be cooked before making tea rice. The flavor of the pan-fried salted salmon is delicious, making it a delicacy in tea rice, worthy of setting aside distractions and savoring. When selecting salmon fillets, gourmets choose the tail part, not only because the fish skin there is tasty, but also because the meat is tender and has a better texture than the middle part."

Trout also comes in various saltiness levels, and the thin slices that look quite shabby are suitable for making tea rice. The salted trout that looks rust-red is the most delicious among trout~ Tear off the hard salted trout meat and place it on the rice. Don't forget to put the trout skin on the rice as well, and then pour hot tea over it.

He also believed that "the most important thing in making bonito flakes is the grater for the bonito, which must be sharp. The best flakes are freshly grated, thin as paper, and deliciously fresh" (from "The Taste of Japan"). He not only had high standards for food but also personally cooked and made the ceramic dishes for serving food. His ceramics were based on ancient Japanese porcelain, and he also created unique styles like "cutting board plates" and "large bowls," which had a profound impact on the Japanese culinary world.

He was outspoken and critical, criticizing gourmets and restaurants, often launching verbal attacks on customers. Behind this was his commitment to the character of a craftsman and chef, even elevating cuisine to the level of aesthetic philosophy. He looked down on coarse, hasty, superficial, and chaotic flavors, believing that chefs obsessed with trivial profits would degrade their character. He said, "Everything must be generous; it won't do without a noble feeling. A spirit that is too lowly is unacceptable." One must have the awareness of a creator: "Whether it is calligraphy or painting, pottery or cooking, what is revealed is actually the author's own image. Regardless of good or bad, one will appear in the work." Although these words may not be pleasant to hear, they are deeply insightful and appropriate for those who have strict requirements for themselves.

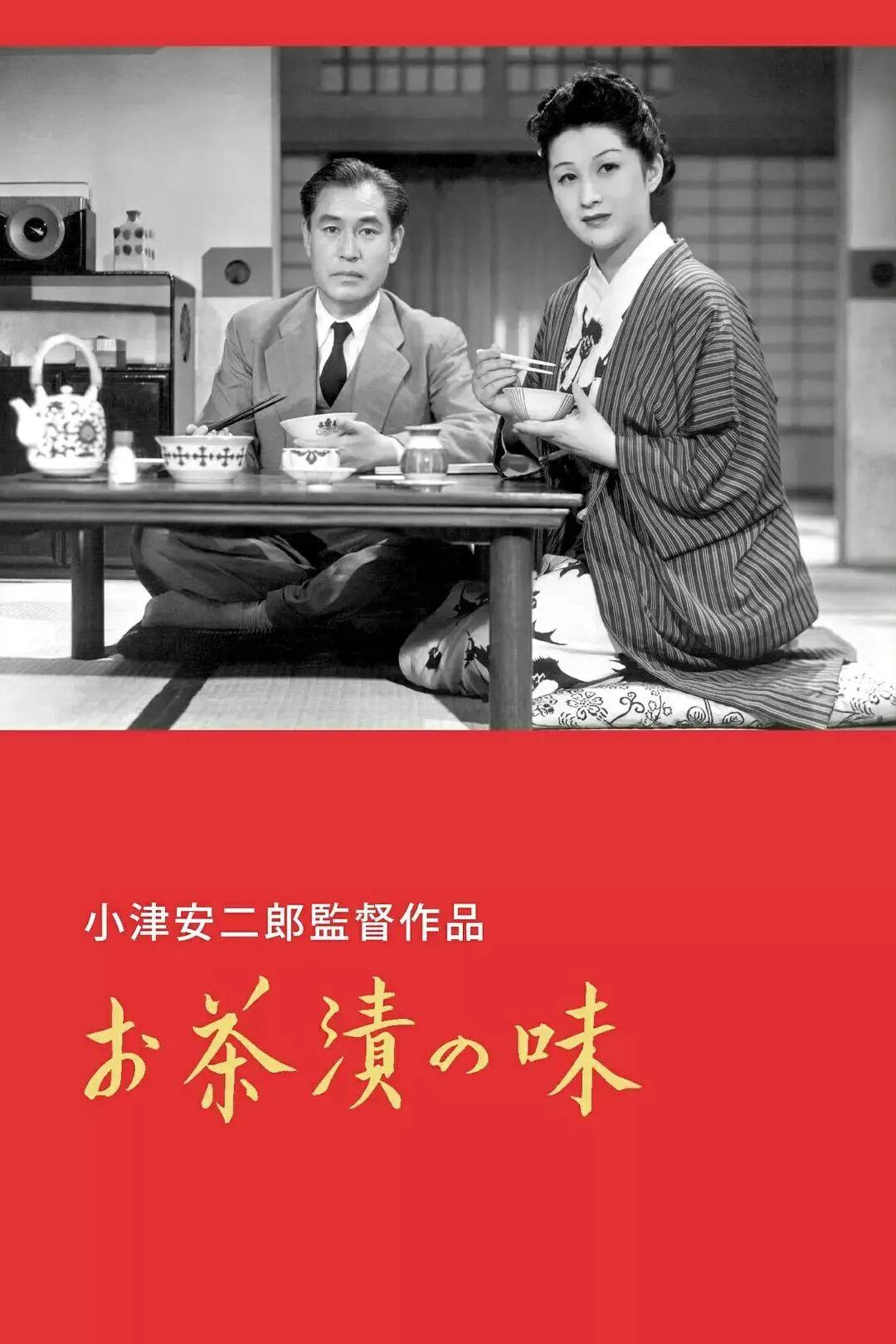

After the release of Yasujirō Ozu's "The Taste of Tea Rice" in 1952, tea rice became a topic of discussion. Ozu's film itself is like a pot of tea, starting off somewhat bitter, like tea leaves in water, gradually releasing its fragrance after a few brews. The stories of ordinary characters are also included in the plain narrative, with the characters' emotions often restrained and hidden until the end, when the true flavor is finally understood.

Ozu was skilled at portraying "family" themes, exploring father-daughter and mother-son relationships in his films, while "The Taste of Tea Rice" revolves around the relationship between husband and wife.

Mr. Shigekichi Satake (played by Noboru Sato) comes from a rural background, quiet and simple. He is the most typical Japanese man, silent and reserved, not good with words and somewhat dull. He works diligently and treats his superiors and elders with respect and obedience. He does not understand romance and would never think of little tricks to please his wife.

His wife, Taeko (played by Michiyo Muro), comes from a wealthy family, extravagant and playful, always with an arrogant demeanor. Taeko looks down on her practical and rigid husband, believing she does not love him and is quite dissatisfied with his way of life. For example, he likes to eat tea rice, smokes low-end Asahi cigarettes, and is accustomed to sitting in third class on trains.

On the surface, the Satake couple does not argue; Taeko speaks to her husband using honorifics and is polite, but their conversations are filled with coldness and rejection. Seven or eight years of marriage have not bridged the gap between their backgrounds; instead, their differing lifestyles have led to numerous conflicts.

Taeko often makes up various lies, hiding from her husband while going out with her former classmates and friends to relax and gossip. Mr. Satake never easily criticizes his wife's capriciousness and extravagant spending habits, nor does he expect her to change. He is well aware of the lies his wife tells to go out and have fun, but he does not expose them, allowing the audience to see his mature, composed, and tolerant side.