No one can predict the future. But, we must try.

In early November, I was invited to speak at the Future Technologies Conference (FTC) in San Francisco. I am very grateful for the opportunity to take the stage and share my research, and equally grateful to be present and learn from others. The quote above was given by the keynote speaker, Tom Mitchell, who opened the conference. While Mitchell's words hold a certain truth, they also invite us to delve deeper into the intricate dance between prediction and adaptability in our rapidly changing world.

Whenever I think about the future, I am reminded of a Bolivian proverb I learned from writer, sociologist, feminist, and activist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui. The saying, roughly translated, goes like this:

The future is behind me. I stand in the present, and all we can see is the past.

It is an initially strange idea, but when unpacked, it reveals a profound wisdom. We can only speak of what is possible based on what has already happened. In Western culture, we often condition ourselves to fixate on the future, constantly reaching for it, trying to predict and shape what is about to happen. However, the reality is that while we can make educated guesses, the future remains shrouded in uncertainty. The inherently unpredictable nature of the future raises questions about the power of self-fulfilling prophecies.

As we delve into the realm of future technologies, this landscape is vast and bustling with innovation. Many breakthroughs are driven by predictive capabilities, often exploited for commercial purposes, such as orchestrating emotional responses in marketing efforts. We are at a time when technologies are being deployed at a rapid pace with little on-site oversight, disregarding potential consequences. It is essential to recognize that these powerful technologies are defined not only by their applications, but also by what goes into creating them, including raw materials and data.

The creators behind new technologies, such as some speakers at the conference, often have lofty intentions, focusing on important global issues like climate change, sustainability, community health, and technologies that enhance individual well-being. However, there is a recurring pattern where technologies veer off unforeseen paths, diverging from their original intentions. This becomes particularly complex when dealing with formidable forces like artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR). These technologies are advancing at a rapid pace, with almost limitless possibilities, along with many ethical concerns.

The topics addressed at the FTC include:

- Deep learning

- Large language models

- Data science

- Intelligence around

- Computer vision

- Robotics

- Agents and multi-agent systems

- Communication

- Protection

- Electronic learning

- Artificial intelligence

- Computer science

In this post, I will provide an overview of my experience at the conference, including the talk I presented and share some highlights from other presentations.

My Presentation

The Future Technologies Conference encompasses a range of topics and specialties, with me belonging to the data science track. My presentation focused on the data mining theme, titled: Reconsidering indigenous data sovereignty: Data mining as a colonial practice. In my talk, I explained what indigenous data sovereignty is and why it is important, before outlining the principles of care for indigenous data governance: collective benefit, authority control, responsibility, and ethics.

To illustrate how care principles can be applied throughout the data lifecycle, I examined a case study to first demonstrate how these principles are often lacking in practical data collection.

A non-governmental organization from Europe came to Burundi to collect data on water access. [1]

The non-governmental organization did not understand:

1. The community's perspectives on real central issues

2. The potential harms of their actions

By sharing public data, including geographical locations, the non-governmental organization put the community at risk.

Collective privacy was violated and trust was lost.

Care principles were violated, especially collective benefit and collective responsibility.

I concluded the talk with some recommendations. Three core data challenges need to be addressed: data collection, data access, and appropriateness to enable access, use, and control of indigenous data and information. [2] It is important to note that there are different local concerns in different regions, although all are negatively impacted and affected by long-standing colonial extractive practices. It is imperative that we continue to educate ourselves and ask broader questions stemming from colonial origins.

It was surprising to me how well it was received and the feedback and questions I received. One question was about the case study I presented. I was asked how exactly the individuals in the case were harmed by data collection that did not adhere to care principles? I elaborated further on how the community in Burundi from the case study was harmed as the researchers ultimately shared their personal data including location data, breaking the community's trust. This demonstrates that privacy is not just an individual issue, but for indigenous communities, privacy is often a collective concern. This may not be considered from a Western perspective, viewing privacy as entirely individual. By expanding our understanding of human values and how they may differ across cultures and regions, we can better understand how data collection and new technologies will impact different populations.

I was very surprised at how well it was received and the feedback and questions I received. One question was about the case study I presented. I was asked how exactly the individuals in the study were harmed by data collection that did not adhere to care principles? I explained in more detail about how the community in Burundi from the compromised case study where researchers ultimately shared their personal data including location data, breaking the community's trust. This shows that privacy is not just an individual issue, but for indigenous communities, privacy is often a collective issue. This may not be considered from a Western perspective, viewing privacy as entirely individual. By expanding our understanding of human values and how they may differ across cultures and regions, we can better understand how data collection and new technologies will impact different populations.

Subsequently, many people approached me and wanted to discuss further about my research. The best feedback I received was simply: Your research is very rare.

That is why I wanted to present this work at this specific conference on future technologies, because many of them rely on data and a lot of data. Data often comes from everyone, and it is very valuable. Some say it is more valuable than any other resource. Most people benefit through the convenience of lessons and applications developed by using public data. However, why are only corporations benefiting from everyone's data? Why is this complete exploitation allowed? Isn't this a form of Neo-colonialism in the workplace? This is the message I received.

Notable Talks at the FTC

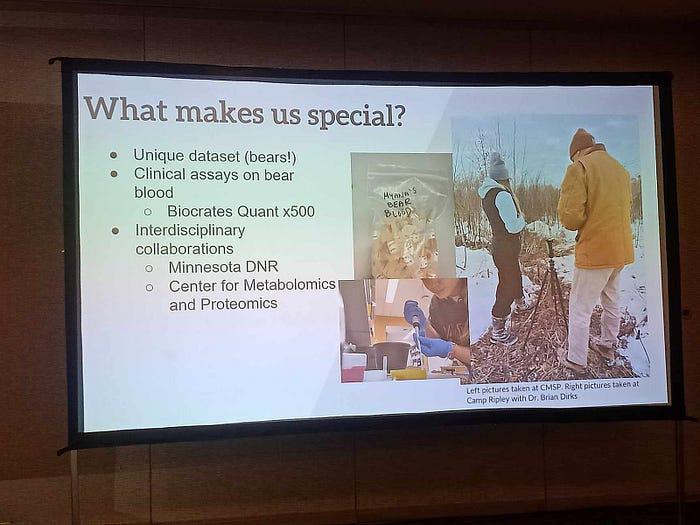

Discussions ranged across the board on new and future technology, focusing on AI, VR, etc. At lunch, I met Myana Anderson, who told me she was talking about Bears. What her talk - the metabolic adaptation in American black bears during hibernation - is that bears have something that humans don't: the ability to be less active for long periods, to hibernate. For humans, our bodies are made to move, and if we are too inactive, we will get blood clots and all sorts of health issues. Her research team and colleagues studied blood samples from hibernating bears to see exactly what allows bears to maintain and balance their internal environment. They collected this data and studied it to see what we can learn to think about treating many diseases in humans related to inactivity and those with conditions that deteriorate with immobility.

This is certainly a unique and intriguing study that has the potential to benefit people with disabilities and immobility-related illnesses. However, there is an aspect that concerns me, in which we are heading towards immobility, where life is lived in VR and people turn into blobs of color and hibernate like bears, because of this research? This was not addressed, but it is entirely my speculation. Is this really the direction we want to go in? Why can't we find ways to continue moving and functioning in our world? Or, is this research really being used only to support those with conditions that force them to be immobile, and not the general population who may sit still for long periods?

It's interesting because it was far removed from my research, but I'm still a bit concerned about how it will be used. It's fascinating to consider a study that doesn't use data from humans, but from animals, and may need to consider the rights of animals in the future.

Another standout conversation for me was called the Avatar's Influence on Gender and Age on Future Self-Esteem, by Marian McDonnell. The study involves using VR to create age-programmed avatars, in an effort to make people more empathetic towards their future selves and save more money for their retirement. The idea is that people find it easy to empathize and care for their parents and children, but not for their future selves. This is true, and they found that this is effective in making people think more about their retirement and save money for their own future. However, the most interesting part of this study is the difference between men and women. When men are introduced through VR to an older version of themselves, they think they look like their fathers, and think it looks neat. When women do the same, they are shocked and scared to see themselves aged.

Women and men are treated socially and culturally very differently with such different expectations, including aging. Older women are not represented as valuable, instead, they are quite invisible, where older men are portrayed as still attractive, as well as having a respectful air that women are not able to achieve. This social discrepancy becomes very clear through their research, and they certainly present it as an important part of the study, which I think is noteworthy. Addressing these inequalities may take more than VR, but it could be an interesting research agency to approach. These deep-seated inequalities make them visible in projects like this, and it provides an opportunity to address them in appropriate and creative ways.

Final Thoughts

Throughout the conference, there were instances where I hesitated to voice my thoughts, observing the prevalent emphasis on pricing speed and volume, and the lack of responsibility and transparency. While some discussions touched on the ethical aspects of technology, especially in environmental applications, the technical details often delved into complexities beyond my social science expertise. It was an opportunity to work on developing my own knowledge in technical fields and sharing knowledge with others in adjacent fields. This is why direct conferences are very important, so that shared knowledge can be integrated and attendees can have a better understanding of what may be overlooked.

As I sat in attendance, moments arose where I wanted to inquire about ethical considerations. In one of these moments, another participant raised a question about similar concerns to mine, only to receive an acknowledgment of lacking expertise in that area. I found this somewhat related, however, it underscores the need for safety and responsibility in what we are building now and in the future.

As we address the rapid developments of the present into the future, certain concerns will certainly arise. Instead of understanding these as worries, restructuring them as long-term visions becomes important to establish checks, balances, and comprehensive protection around emerging technologies. This includes considerations not only in the implementation process but also at the early stages of the data lifecycle, ensuring protective measures at all levels without unintended consequences. The question still remains: Can we minimize the potential harms associated with new technologies, or are some levels of harm unavoidable?

Currently, there is an opportune moment to integrate ethics into technology discourse. However, what is imperative is to approach this integration with an awareness of historical context and existing systems. This nuanced approach is necessary to navigate ethical considerations in a way that acknowledges the complexity of past and present systems.

References

. Stories told and marriages about data sharing in Africa. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 329 Phản41. Virtual Event Canada: ACM, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445897.

[2] Rodriguez, Oscar Luis Figueroa. Indigenous policies and indigenous data in Mexico: context, challenges, and perspectives. In Sovereignty and Indigenous Data Policies, 130 trận47. Routledge Studies in Indigenous Peoples and Policy. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021