Efficiency can be defined as doing things correctly, and it can also be done within a reasonable time. We are striving to improve our work attitude and are prepared to disrupt our work-life balance to produce more output. To enhance our efficiency, we tend to root out activities that do not increase the required workload. No breaks, overtime is needed, X must be completed, lunch can be enjoyed at the desk, and so on. Constant efficiency growth becomes a primary goal. Tools that should be instrumental become crucial.

In this article, I want to consider some dark sides of efficiency and why we should be cautious.

Definition of Efficiency

Efficiency at a simplified level can be defined by the following formula:

我们认为, Effort是一个人完成的总(!)完成的总计,而Time是努力时的时间插槽。就目前而言,有两种增加上述因素的方法。通过在给定的时间插槽内产生更多的输出(选项1),或通过维护努力示波器(选项2)来减少时间插槽跨度。尽管我们有两个选择,但它们通常都会产生更多的“全局”输出。即使我们减少任务所需的时间插槽(选项2),还将获得的时间插槽用于新活动。

The above definition can be referred to as objective. There is another interesting perspective. When we assess someone's efficiency, we rarely have access to information about how much time was spent on a given effort. We usually only see its effect - the output generated.

I call this apparent efficiency.

People can hide retained time to create the impression of efficiency growth. From this perspective, we can "improve" efficiency through overwork rather than by improving work processes.

We have completed the definition. Now, I will turn to situations where efficiency growth can get us into trouble.

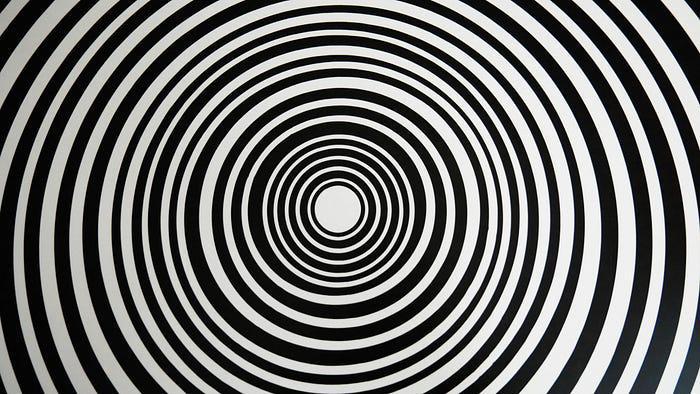

Efficiency Spiral

Oliver Burkeman claims in his inspiring book Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals that optimization and efficiency growth often lead to additional work. As a result, efficiency spikes often expand our to-do lists.

Of course, we have no problem working better or faster. The problem begins when improving efficiency becomes the primary goal of our activities. In this case, we mainly derive enjoyment from the increased pace of work. It can create a spiral that leads to burnout. At some point, you cannot speed up or even maintain the pace, and thus your main source of enjoyment (increased efficiency) disappears. If you cannot find alternatives that bring joy, you may encounter burnout. To avoid the spiral, we should treat efficiency as a tool and care more about effectiveness.

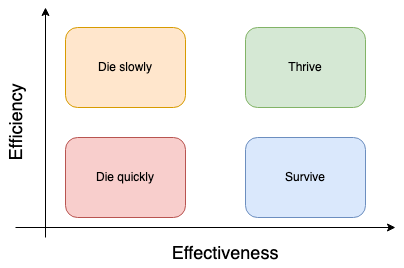

Effectiveness vs. Efficiency

The root cause of the above spiral is that we tend to confuse effectiveness with efficiency or view them as synonyms, while they are essentially different concepts. Effectiveness is about setting goals and making decisions. It operates at a strategic level. In terms of efficiency, it is merely an implementation tool, a tactical tool. You are effective when you are heading in the right direction. Following the direction correctly is the domain of efficiency.

You might discern the difference through the following example. When analyzing people's career success, you will find that many excelled in school but did not realize their potential in the job market. Individuals who do not have issues with working efficiently often excel in school because they have not decided what they want to do. They have supervisors and teachers who set the direction, and the best students work hard to follow it. The situation is entirely different when you have to choose a major in college or a job position. When the field you choose of interest is not profitable or has almost no job opportunities, correct implementation is not enough. Even if you master something, the current market does not need it. Your decision may be poor or unfortunate, and high efficiency cannot change your predicament.

Another example is the Scrum Sprint method. No one denies that the speed of the development team is an important factor for sprint success. But this is only useful for sprint goals. When our main focus is on delivering more story points than in previous sprints, rather than considering the results to be achieved upon completing the current iteration, we run into problems.

Effective Stagnation

Effective stagnation is a situation where we remain in our comfort zone simply because we want to fulfill our duties more efficiently. We are performing the same or similar tasks but feel frantic about the faster pace. Thus, we abandon new challenges and are not interested in broadening our horizons because all energy is directed towards increasing the speed of current repetitive activities.

Underestimating Breakthroughs

Our efficiency dreams can represent a situation where every minute of our working time is utilized effectively. We have no idle activities, such as breaks, social meetings, or midday naps. We have an ideal workday without unnecessary "disruptions." Daniel Pink argues in his interesting book When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing that this approach often backfires on both short-term and long-term efficiency. Our attention and focus are depleted during mental activities to maintain clarity, and we must recharge frequently (breakthroughs every hour). Good breaks can be refreshing and improve our performance:

- Social breaks - Talking with colleagues is a great way to improve mood and relieve stress

- Non-technical outdoor breaks - Putting away the phone or laptop and taking a walk can boost motivation and concentration

- Naps - Done correctly (10–20 minutes) can enhance cognitive performance and improve mental and physical health

Everyone has different dynamics throughout the day. We have peaks, troughs, and rebound times. When you know your performance will naturally drop, it is a very good idea to find out when you peak and place the most intensive tasks during that time.

Conclusion

Feeling busy and producing a large amount of output is often a deceptive measure of productivity. It is absolutely a good idea to occasionally take a step back and consider the meaning of having meaningful work rather than improving efficiency at all costs.

"Nothing is as useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all."

P. Drucker