However, before the sailing ship set out to sea, he succeeded in mastering these late reflections. He told himself that it was safe, having passed through many voyages and withstood many storms. It was unfounded to believe that it would not safely return home after this trip.

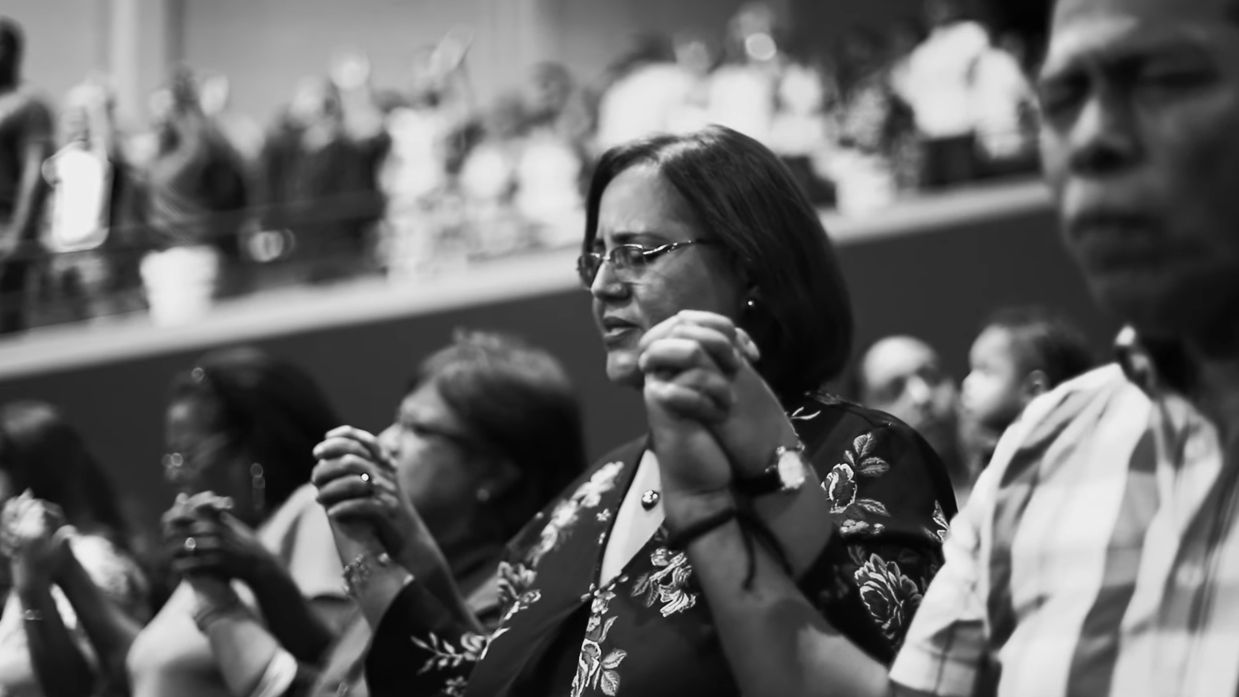

1. Faith:

He placed his faith in the protection of God, who rarely fails to safeguard all the unfortunate families who have to leave their homeland in search of better fortunes abroad. He would dismiss all petty doubts from his mind, due to the honesty of the workers and contractors. Thus, he had a comfortable and sincere belief that his ship was safe and capable of going to sea. He watched it sail away with a light heart and merciful hopes that the expatriates would succeed in their distant new homeland. And he had to collect insurance money when the ship sank in the ocean.

The origin of faith is a big question that not everyone thinks too much about. Some beliefs are formed simply as a springboard, a premise for people to explore and discover the more practical or greater aspects of life. There are beliefs that belong to religion, existing in a person simply because they were born and raised in an environment influenced by taught religion. These religious beliefs, in their process of growing up, ultimately, we need to have something to believe in, a foundation that acts as a lighthouse, a guiding flag for oneself amidst the storms and traps of life. This is also because seeking the origin of faith means you have to ask questions about that very faith, sometimes even having to dig deep to the roots of the belief. Therefore, to understand faith from a spiritual and scientific perspective, let us explore in the article "Science and Faith" by author Hù Vũ.

2. Courage and time:

But we have far too many more important things right in front of us to worry about. So rest assured that not everyone has enough courage and time to find out what true faith is, except for people like William K. Clifford, an English mathematician, and William James, an American psychologist. The two debated faith, a difficult philosophical topic that sparked much controversy. In 1877, Clifford wrote an article titled "The Ethics of Belief" in the Contemporary Review, in which his famous argument was that "it is always wrong, anywhere, with anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence." He argued that each of us has a moral responsibility to verify our own beliefs and gather sufficient evidence before we have the right to believe in them.

In the story told, the shipowner, although fully aware that his ship was too old and unsafe, still decided to send it out to sea. He suppressed his own doubts about the ship's reliability and continued to let it go, even when someone had warned him about this issue. He believed that because the ship had weathered many storms and returned safely many times before, this time would be no different. When the ship sank and took the lives of all those on board, Clifford believed that the shipowner must be held responsible. He charged the shipowner that his belief, no matter how strong and sincere, could not excuse the consequences of that irresponsibility.

Because he had no right to place faith without sufficient evidence. If someone objects that "I don't have time to research all the materials," Clifford would succinctly reply, "then you also don't have enough time to have faith." He then received a response from Harvard psychologist William James. In the essay "The Will to Believe" in 1896, James argued that sometimes we can or must form beliefs without sufficient evidence for them. For example, in moral decisions, we often face two opposing values and can only make one choice. This view is supported by Julian Berini, the founder of the philosopher magazine The Philosophers' Magazine. James also emphasized that our will can influence decisions in certain specific cases, but it often does not directly affect our beliefs.

3. Principles of life:

And if your principle of life does not allow you to place faith in anything without sufficient evidence, you are also simultaneously experiencing the benefits that a truth, if it exists, brings. I believe that for us in many cases, our beliefs are essentially a transferred, entrusted, or inherited belief from others, or in other words, our beliefs and those of others differ somewhat. This shows that we mostly do not think logically about our own beliefs, and that is the basis on which Clifford presents his argument as stated above.

Although somewhat extreme in seeking evidence for his beliefs, cosmologist Stephen Hawking also shares a view very close to Clifford. In an interview in 2014, he openly admitted to being an atheist as stated in his book "The Grand Design" with Leonard Mlodinow in 2010. Hawking did not hide his intention to build a theory for his entire Theory of Everything and declared that humanity could understand everything in this universe and that science has developed enough for us to understand that this universe does not need God to exist and evolve.

Along with Clifford's perspective, besides Stephen Hawking, there are other deep scientific researchers of the modern generation such as Carl Sagan, James Jeans, Alan Turing, or Neil deGrasse Tyson. Most of them do not adhere to atheism and do not follow materialism. This is often a prejudice of many people about scientists, although each of them shares a similar view on faith, but most recognize that they adhere to agnosticism, rather than atheism.

In Carl Sagan's book "The Demon-Haunted World," he presents a hypothetical situation that I find very interesting. If he now tells us that there is a fire-breathing dragon in his garage, when you say you don't see the dragon, he will reply that this dragon is invisible. If you suggest sprinkling flour on the ground to see if there are any dragon footprints, he will respond that this dragon is hovering in the air. If you suggest using an infrared camera to see the invisible fire that the dragon breathes, he will say that the fire of this dragon is non-thermal and continues to provide reasons why the experiment will never succeed. He concludes that the difference between an invisible dragon hovering and breathing non-thermal fire and the absence of a dragon would be what. If there is no way to prove he is wrong.

If there is no experiment to counter it, what significance does it have for me to say my dragon truly exists? The fact that you cannot prove that my hypothesis is wrong does not mean it is true. Similarly, in James Jeans' book "The Universe Surrounded" in 1929, the physicist opposed the idea of humans using science as a tool to prove the existence or non-existence of God. He explained that if we consider the universe as a painting, going back in time will not lead us to the birth of that painting, only to one edge of it.

4. The birth:

The birth or origin of the universe is beyond our understanding, just as the way an artist is outside their painting. If you ask about the nature or meaning of everything, many people, and most scientists from the 19th century and earlier, would roughly answer that "Everything has always occurred logically and systematically." If we try to go back to the moment of the Big Bang and observe how everything was born, we would understand the nature of everything. Or if we magnify everything to the largest size and study quantum dynamics, we would also understand the nature of everything. Because everything, after all, is just a large system based on rigid, immutable principles. This is also the main philosophy of Copernicus's argument, and David Mermin had to exclaim that "If I had to summarize the content of Copernicus's argument."

It would be to mouth and calculate, this worldview has been heavily criticized by scholars and scientists from the 20th century onwards when questioning the formation of human consciousness and the emergence of quantum physics. Physics has begun to be analyzed recently. There is an article in Scientific American that I encourage you to read titled "Materialism Alone Cannot Explain the Riddle of Consciousness" by Adam Frank, a professor of astronomy at the University of Rochester, New York. He writes that in the quantum world, where the nature and position of matter are no longer deterministic but have now become a spectrum of different possibilities, the collapse of materialism in science is closer than ever.

And if Newtonian physics can explain the movement of blood through blood vessels and chemical diffusion across synapse neurons, it becomes fragile and weak in explaining the non-material phenomena of consciousness. If we cannot find the nature of consciousness or at what level consciousness appears in intelligence, then we are far from being able to answer the emerging philosophical questions and hypotheses, such as artificial intelligence and the possibility that they will put an end to human life. After all, faith is a concept that is both emerging and easy to define.

Although it is difficult to pinpoint exactly for each person, ultimately, all beliefs in life will face disapproval, even from the universe itself, whether your name is related to science or not. Every time I hear lectures or book introductions by Professor Trịnh Xuân Thuận, I always find the discussions last for an entire hour, thanks to the contributions of those who deeply study philosophy and young people passionate about science. Some say that philosophy is dead, while others assert that without philosophy, science becomes meaningless. In reality, it is unclear whether this article intends to support or oppose any philosophy, but it only hopes to clarify what has been and is happening in the relationship between philosophy and science.