This is F's.

Closet is a mess. But I have an article to write. I peck at a sentence, change a few words, and then delete it. I do the same thing a second time. I check my email. Then glance at my phone. Suddenly, I’m buying “the amazing eye cream that’s finally back.” I force myself back to the paper. But how can I write when the eye cream might be out of stock again?

Also, the closet is chaotic. I close my laptop and head to the hallway.

Most of what’s there is not (it’s a shared public closet with our neighbors), but some is. Beyond my awareness. There’s a box of Halloween stuff to decorate with the kids from our neighbors. Stop. Under that box is one I half-recognize, a large translucent plastic tub filled with colorful shapes, as familiar as a blurry face in an old photograph.

I drag it to our apartment, open it, and feel delighted. We wonder what we did with Ava’s Barbies. I want to think we stored them neatly somewhere, tucked away in their patent leather dreams. But no. I smile at the yellow hair, exposed limbs, and glittery fabric.

I thread a green floral taffeta dress between my fingers. This is the one Barbie (Ava) wore on her first day of Pre-K when she was told she could bring a “comfort toy.” When I suggested she might want something softer and easier to confuse, she looked up seriously and said, “But I love Barbie.”

Who can blame her? I love Barbie too.

The taffeta between my fingers is stiff, but it’s clear that others are too. Stinky.

I take a breath and realize my hands are full of a crispy, glittery mixture. I look closer, gasping. One Barbie is covered in rotten spots, her face and dress splattered, as if she crawled through dirt to get to the ball. I notice those little braids that make up her face and feel sad that I don’t remember if it was me or our nanny Thelma who helped Ava make them. Her arms are raised as if waving, or saying, “Hey. Do something! We’re rotting here!” The scene is so morbid that I can’t help but think of writing a Greta Gerwig Halloween spinoff.

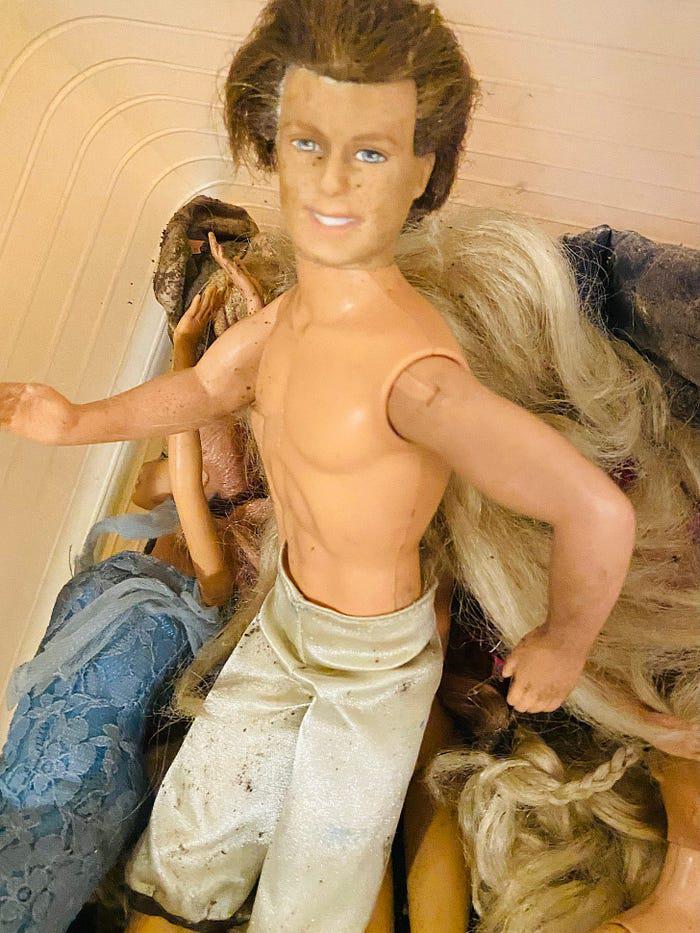

Ken doesn’t fare any better, though he manages to strike a bare-chested pose, which is part of a heroic dance move. Either way, he looks cool in his five-pocket pants, and his optimism is touching.

Without mold, he would be ten.

Cramping, I poke around. Despite the Barbies being moldy, they still try to maintain an air of dignity. Especially one exposed, wearing three strands of pearls, crossing her legs at the ankles.

However, my eyes are drawn to the exposed Barbie underneath. It looks completely rotten, very familiar. I push past it bare. Sailor Boy. My first true love. When I was four, my grandparents brought him back from a cruise, and I quickly fell for him. His fluffy hat reminded me of the Pillsbury Doughboy’s hat, but Sailor Boy was more masculine, even roguish, even as I shoved him aside and let him fall on his forehead (dangerously!). As he tilted from horizontal to vertical, his blue eyes opened and closed. I found his teeth charming, even though I didn’t know that word yet. Seeing him now almost breaks my heart. My Sailor Boy has been rotting. In fact, I bet any moisture that got into that tub was absorbed and spread by him. A bad apple. And I thought he was so sweet. Even so, I’m glad to assess the boyfriend.

Still, I give my super citizen bad boy one last adoring glance, then sigh and pull the trash can out. I watch the Barbies fall, a rotting beauty in another rotting place, my eyes drawn to those pink things that fell on the pile. I hold my breath and pull it out. I immediately realize. The sweater my mother knitted. I scan the Charles Manson scene and pull out a matching pair of shorts.

Suddenly, the more obvious knits turn into scraps. Like you notice a water tower in New York, you realize they’re everywhere. A white cardigan and pink ruffled decorations stare back at me. A purple pencil skirt. And a strapless dress with a deep green belt; Ava’s favorite.

The knitted scraps didn’t cover the decorated Barbies and my ex’s moldy spots, but they surely would reveal. I filled a bowl with water and white vinegar, then tossed them in, regrettably dragging a bag of stinky Barbies down to the basement.

As they soaked, I thought about how my mother gave Ava her outfits, saying, “These might not be as fancy as the others, but I made them, thinking you might…” I was ready to intervene on how to say they were beautiful, but I didn’t need to. Ava’s face lit up, and she gasped, “Oh, Grandma!” That made my mother smile, and I felt proud of my little girl. She loved the shiny, bright pleated dresses of Barbie, but when she saw it, she knew beauty.

I fished them out of the bowl, their smell still making me recoil in disgust. I squeezed them out and then tossed them into a fresh batch of vinegar mixture. The sweaters and clothes floated, and I thought of the red shift my mother sewed for Barbie. I loved its bell sleeves and was fascinated by the seams that pointed to Barbie’s perfect bust.

“What are these?” I asked.

“Oh. Those are darts,” my mother said. “To give the clothes the right shape. Near her bosom.” I didn’t fully understand, but found this talk about breasts and darts excitingly adult and feminine.

My mom was always doing things. The night before my 11th birthday party, as we finished the dishes, she announced she was making pizza from scratch. I was terrified. In the early 70s, birthday parties in suburban New Jersey were all about pizza, but the kind that came out of a white box. Not the kind my mom made from a kit.

“Why can’t we just order one?” I spat. “They’ll think I’m a loser.” Her eyes flickered with a hint of hurt, but I didn’t care. “Why can’t I have a real cake anymore? Like, from a bakery?” I continued. “Audrey had a huge one. She said it was called cake.”

My mother turned to the kitchen sink, tightening a faucet that didn’t drip. She said, “I think we can get an ice cream cake.”

I knew the chocolate leaves were in the fridge, ready for the top of the cake. I helped her make it. We washed the leaves we cut from the rose bushes in the yard. As we patted them dry, she always said the little ones were the prettiest. We poured dark chocolate over them, licking our fingers with our identities. Once frozen, we carefully pulled the leaves from the chocolate, forming precise replicas, veins, stems and all.

The leaves looked like these, but smaller and shinier.

As a child, I thought she was magical. On the 10th and 364th days, I wished she could be as cool as my friend Nancy’s mom, who wore two-piece suits and looked exceptionally chic while smoking on a lounge chair by the pool. I discovered about friends’ mothers, from their frosted lipsticks to their ash-blonde highlights, to the oversized sunglasses perched on their heads, thrillingly. My mom was beautiful, but she didn’t wear liquid black eyeliner. She taught second grade. She always looked nice, but she shopped on sale and wore reliable one-piece Jansens at the swim club. She was tall, thin, beautiful, and radiant. But she was a wise mom, not a glamorous one.

She turned around, forcing her lips to smile. “Homemade cake isn’t your style anymore?” she asked. I had no style. I was 10. But when I saw them, I did know the feeling of hurt.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered, because if I tried to speak, I would cry. She no longer fidgeted with the faucet, wrapping her arms around me.

“It’s okay, sweetheart,” she said. I loved it when she called me “sweetheart.” It made me feel adored and safe, without any other words needed. I wrapped my arms around her, buried my head in her embrace, soaking it, the darts and all.

The next night, my mother pulled the pizza from the oven like a prize. My friends and I said “Oh, wow” and “far out,” trying to sound like Laurie Partridge. There was a bottle of Coke on the table - not the store-brand or ginger ale we usually had (only on special occasions, like when we had hot pastrami sandwiches on summer nights). I knew, and quietly loved her.

She warned, “Be careful, it’s hot.” I couldn’t help but hope she wouldn’t sing. But only for a second. She cut into the crust with impressive precision. We agreed the pizza was as good as the piano piece.

“Better!” Nancy said. My mom’s eyes met mine, and I felt so proud I had to look away.

His stench was falling, but the Barbie clothes needed another rinse and more vinegar. They floated on top, and I poked them down with a spoon.

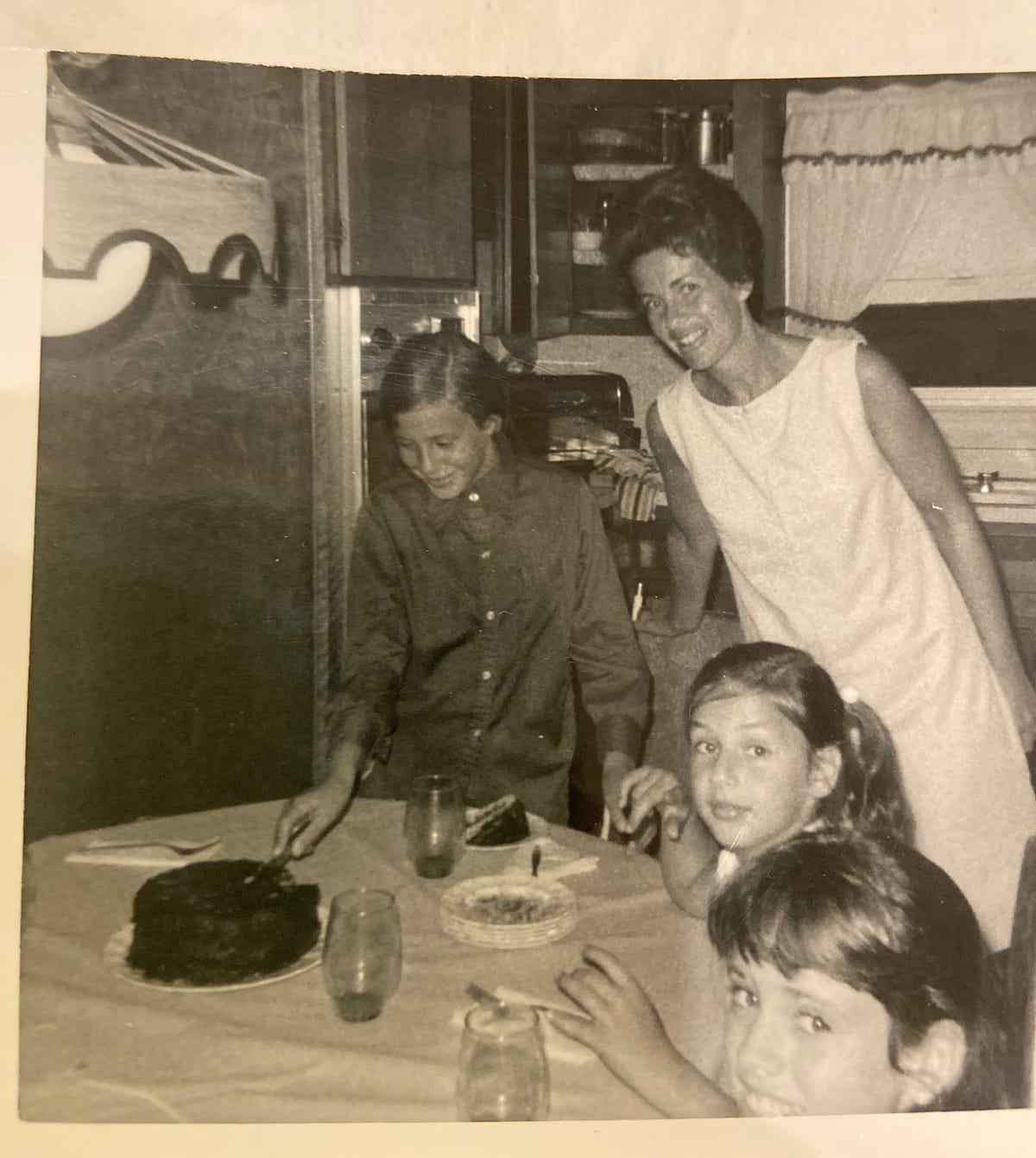

I haven’t had a photo of my mother since that birthday, but when I was young, I did have a photo from another birthday, trying to tame summer frizz with a tight ponytail. Combined with my button-down shirt, it made me look more like a boy, but my mom looked like a woman, her beauty - the kind of hair that was considered sunscreen when Bain de Soleil #4 was the thing.

Around that time, I started calling her “F.” At the end of the school year, a group of parents gave her a briefcase with her initials in gold. It was different for her, but she took it to school, and it was once a good sport.

“Have a great day, FF,” I said before school let out, which made her laugh, so I kept doing it. At some point, it became F, and it never changed.

She no longer did things, as those busy hands were too weak to even bring a fork to her mouth. I fed her pigs with a blanket and a mini potato knife, and we laughed, we laughed, we always liked the appetizers at weddings more than the food.

“Do you remember how you made the leaves for the cake top?” I asked.

She smiled and nodded. “The little ones are the prettiest,” she said softly, our eyes meeting.

“You are the prettiest,” I said, and she shook her head but smiled.

I told her about the Barbie clothes and showed her the pictures. She asked if the smell was gone, and I said it was.

Then we fell silent, as those days often are for us. When your life reduces to bed, bed, bed, there’s nothing to say. So I talked about work and the kids, and she nodded.

Then I thanked her. Love. Ridiculous. Kind. She shrugged as if someone could be those things.

“For everything you’ve done,” I said.

“What have I done?” she asked.

I said, “These paintings that adorn the walls of her house, hanging landscapes, seascapes, and portraits of old men. As I listed other things, I pointed with my fingers - “Afghans, sweaters, candlesticks, and platters.”

She shrugged again modestly, but with a slight smile.

“And the way you wrapped brownies in wax paper for my lunch box or the way you charged the room. Other kids had those pink snowball things and Twinkies, and they traded them, but I never traded my stuff because it was too good.”

She laughed a little.

“And always a good egg.” She smiled at her hands. She said, “Sometimes I was a little disruptive.” Her eyes sparkled for a second.

“For me, sweetheart. To keep me safe.”

We watched a YouTube video of Liza singing “Cabaret,” and she whispered “Wonderful,” just like she always did. Then we listened to Louis and Ella sing “Cheek to Cheek,” and I held her hand, dancing in front of her chair. As he sang, we trembled with Tevye’s huge body around the barn, “If I Were a Rich Man.” Even though we knew it was silly - maybe because we knew it was silly - we applauded.

Then I had to catch a train. Back to New York. And leave the gentle glow of her smile. Until next time.

I was about to edit and post this when I got the call I had feared and prayed for ten months, that it was time. Finally. Her suffering ended. She was not her ending.

But it was far from over.

On the other end of the phone, the voice’s end. The end of her calling me sweetheart. The end of feeling safe. The end of quiet afternoons holding her hand.

The end of being a daughter.

The next morning, her sleeping eyes remained closed, and she died in her own way like a lady.

When we buried her, the rabbi not only needed a shovel, but we covered her with enough dirt so you could no longer see the coffin. My siblings did their part, and I did mine (poorly). We watched our children, spouses, friends, and relatives take turns grabbing the shovel, stuffing our dear mother into this long and final sleep. It lasted longer than we could bear, but when we finished, the rabbi spoke about the importance and healing quality of burying loved ones, not with machines but with our own hands.

Though those memories of the cold wind will haunt me forever, there’s also a part that soothes me. Because his words made it so fitting. For someone who did so much for us, this was the last thing we could do.

With our own hands.

And her attitude.

And her loving heart.

Goodbye, dear F.