During the Heian period, in the Nara era, which corresponds to the Sui and Tang dynasties in China (early Tang), "Tang fruits" and their production methods were transmitted from the Chinese mainland to Japan. The envoys and monks sent to Tang brought back 8 types of Tang fruits and 14 types of fruit cakes, but from a modern perspective, it is hard to consider them as snacks. Originally, they were mainly made from flour (wheat flour) in China, but in Japan, they evolved to be primarily made from rice flour, flavored with sweeteners, and deep-fried into shape, initially used as offerings in temples. Gradually, they spread among the nobility and became popular. Wagashi has many elegant names, such as "Asadew," "Tsukireiko," and "Nishikiyokan," which were named by the Japanese imperial family and nobility, inspired by Waka poetry.

In the mid-8th century, Jianzhen brought sugar and honey from China. After entering the 9th century, Kukai brought back red bean seeds from the Tang dynasty, which were cultivated by a confectioner named Wataru in the vicinity of Saga Okurayama. After being cooked with sugar, he designed Ogura filling (おぐらあん).

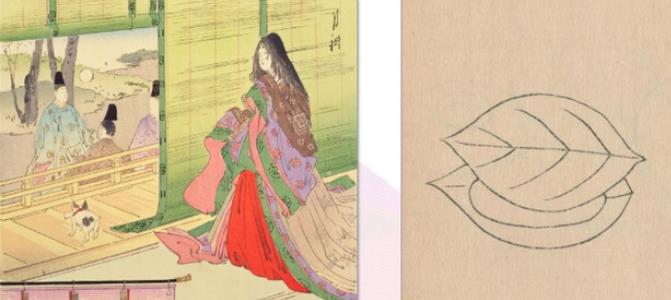

In the late Heian period, with the introduction of Zen Buddhism, wagashi became closely associated with tea-drinking etiquette centered around Zen temples, and a unique "tea-drinking" culture developed. In "The Tale of Genji," there is a food called "Tsubaki Mochi." The story is about offering Tsubaki Mochi to people after a game of kemari.

In Muro no Miya's "Jigai Nihon," the entry for "wagashi" states that Japanese women love sweets. The "shaved ice poured with sweet syrup into a new metal bowl" mentioned by Sei Shonagon in "The Pillow Book" is the predecessor of modern shaved ice. The sweet syrup is a natural dessert extracted from vine plants, squeezed out in autumn and winter, and can serve as a substitute for sugar after concentration.

Monks who traveled to the Song dynasty brought back the teachings of Zen Buddhism and new popular food culture to Japan. With the spread of Zen, Zen monks would go to tea houses to drink tea and eat snacks (not full meals) after finishing their main meals in the morning and noon. "Ocha to wagashi" began to coexist and became a unique Japanese tea-drinking habit, leading to the formation of tea ceremony culture.

The illustration in "Mogui Ehon" conveys the situation of a poetry gathering during the mid-14th century Nanboku-chō period. Across the corridor, the kitchen is preparing food for the tea gathering. A monk in the corridor is holding a large basin with the tea snacks of that time.

From the 15th to the 16th century, the tea ceremony was basically established. According to records of tea gatherings at that time, the "snacks" in the tea ceremony often used fruits and nuts such as persimmons and chestnuts, as well as rice cakes, yokan, red bean paste buns, and tofu grilled dishes.

During the Meiji era, Western culture spread rapidly in Japan, greatly influencing wagashi. The use of Western cooking utensils brought significant development to wagashi. For example, with the advent of ovens, baked snacks like chestnut buns and cake buns mostly emerged after the Meiji period. At the same time, Western ingredients such as butter, milk, chocolate, and cocoa also infused wagashi with fresh flavors. Japanese wagashi artisans combined tradition and modernity to create many high-end wagashi.

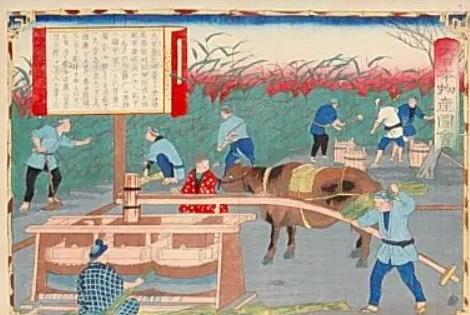

Sanuki Country White Sugar Refining Illustration

The first American minister to Japan, Harris, visited Edo to meet Tokugawa Iesada, and the gift he received was wagashi, which was beautiful both in external decoration and internal sweetness. The literary master Soseki Natsume liked to break a red bean bun into four pieces, placing a quarter of the bun on white rice and pouring hot tea over it to eat.

Seeing the vibrant wagashi makes one's mouth water. Traditional Japanese sweets and pastries are very healthy because their main ingredients are rice flour and beans. The bean paste mixed with sweet sugar is extremely delicious.

The small wagashi represents the culture and spirit of the Japanese people. In Japan, wagashi is a tea accompaniment. Japanese people drink matcha with sweet wagashi, which has some health benefits, as the sugar can offset the stomach-cleansing effect of bitter tea.

There are many varieties of wagashi, which can be roughly divided into: namagashi, han-namagashi, and karagashi. For example, mochi belongs to namagashi, and during New Year or festive occasions, families will pound mochi. When travelers see the scene of pounding mochi, it evokes feelings of homesickness. The skin of "Momoyama" is made from traditional golden skin, with an enticing golden color and delicate texture. The filling incorporates the deliciousness of milk or chestnuts, making it refreshing and not overly sweet. It belongs to han-namagashi. Snacks like wheat senbei, rice crackers, salt-baked goods, and tamagomatsu belong to karagashi.

There are also rice crackers made from a type of glutinous rice; dango is made from a small amount of glutinous rice flour, and both of these snacks are loved by children. "Zenzai" is made by adding adzuki beans and rice cakes to a thick, sweet soup. Yokan is made by steaming red beans, flour, and kudzu starch until solidified, resembling a meat stew. "Rakugan" is a type of sweet made by pressing sugar into wooden molds, without adzuki beans. Rengetsu is visually pleasing and often appears in tea ceremonies.

Wagashi is considered the flower of Japanese food culture, partly because of the charm of "handmade," which embodies the allure of "heart." Wagashi pays great attention to seasonality, and many types of wagashi only appear in their respective seasons. Each brightly colored and uniquely styled wagashi embodies the creator's feelings about the season and their pursuit of color, fragrance, taste, and texture. The coexistence of wagashi and the tea ceremony creates a harmonious relationship, allowing one to feel the tranquility of the moment.

A small wagashi encapsulates the brilliance of nature in its ingredients, colors, and shapes, quietly reminding you of the changing seasons, serving as a small messenger conveying the cycle of the four seasons in life, evoking an incredible response within. For example, the "Sakura Mochi" in March represents the spring wagashi. The "Shuukusa" in September derives its name from the chrysanthemum's alias "Kusanaruji" (the lord of grass). Chrysanthemums have been loved by people since ancient times for their noble character. It is a type of yokan with a white filling.

"Monaka" is a type of wagashi that originated in the Edo period, named for its shape resembling a full moon, referring to the moon on the night of the 15th. It is made by grinding glutinous rice into flour, steaming it, and then shaping it into thin chrysanthemum or plum blossom shapes or squares, and then baking it. The "Yuzu" shape in December has been loved by Japanese people since ancient times, and there is a custom of taking yuzu baths during the winter solstice in December. The "Yuzu" shape is made by adding grated yuzu peel to the dough.

If you want to enjoy the best flavor of namagashi, it is best to eat it when it is freshest. If stored in the refrigerator and then eaten, the taste will not be good, and the wagashi will become hard and dry. If you plan to eat it on the same day, just keep it in a cool place; if necessary, freeze it, but it is recommended to place the wagashi in a sealed container and let it thaw naturally when ready to eat. After being frozen, wagashi should be eaten immediately after thawing, and definitely should not be refrozen!

In Japan, wagashi plays a very important role at various stages of life, from birth, schooling, marriage, to death. It is often the most charming gift for friends and family. Wagashi has a lovely appearance, exquisite craftsmanship, and melts in the mouth, bringing a feeling of happiness from within. Those brightly colored candies are the favorites of little girls, and giving a box of such candies as a gift for a classmate's birthday is a great idea.

When traveling for business or tourism, it is also essential to bring back some local specialties, among which wagashi is a must. Each region's wagashi has its own characteristics and unique flavors. Giving it to family or friends is not only a courtesy but also represents your heartfelt intentions. A small wagashi encapsulates the essence of that place, and savoring it reveals a unique taste.