Memories of the music that escaped

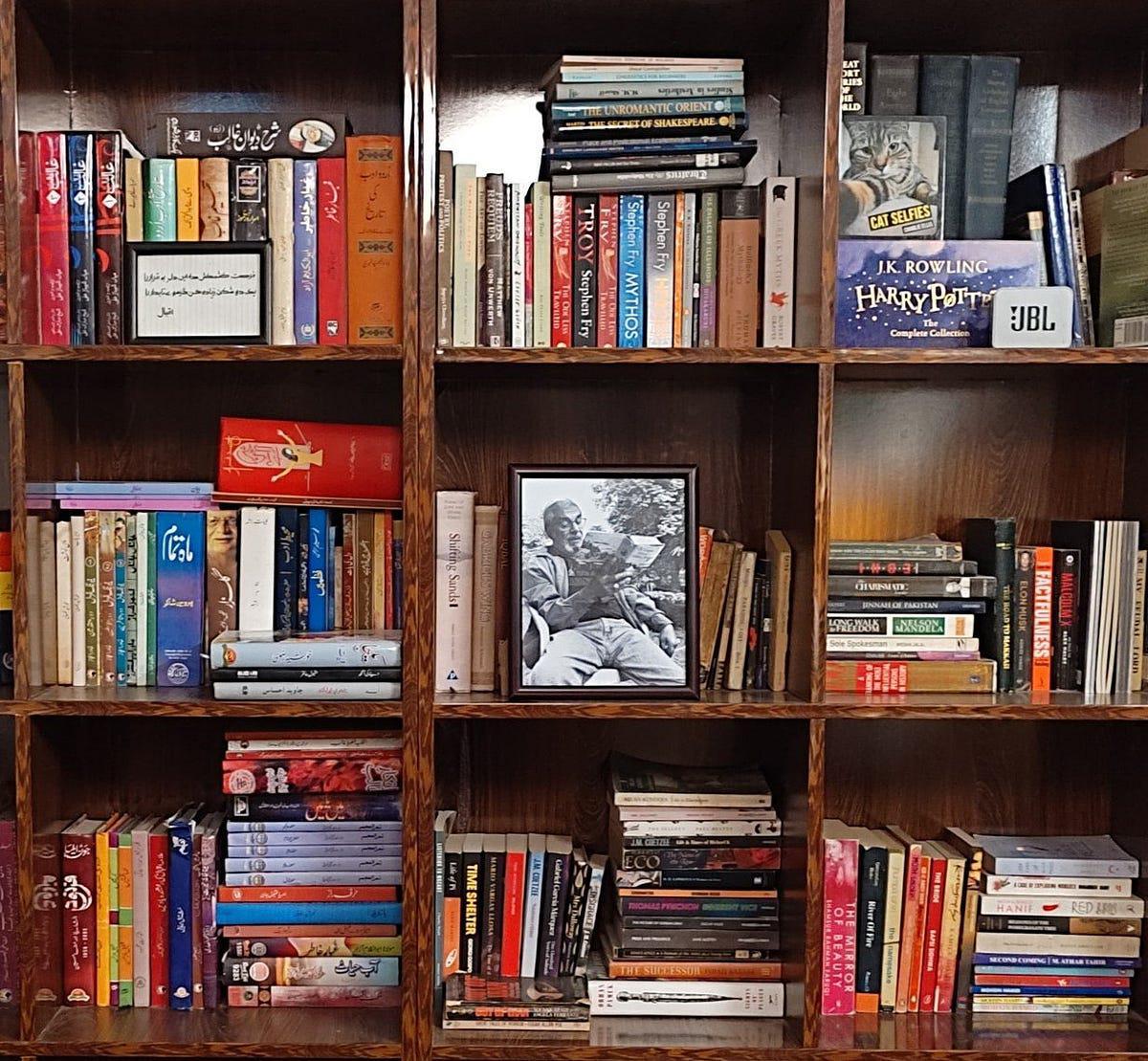

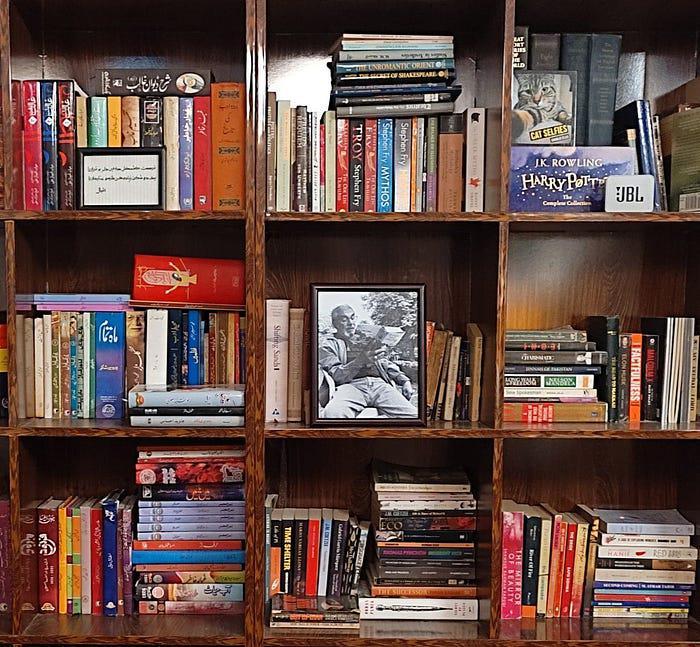

Binet: The evening hues of Lawrence Garden slip his image in when he sits inside the frame, slightly bored to the left in an uneasy chair. He is wearing his jeans and a warm gray upper, holding a thick sacred volume of Shakespeare's complete works. A cigarette, almost cursed with mortality, dangles from his fingers. He seems engrossed in the pages - I am tempted to think it's the sonnets he's reading. It's because he says it was his wish to teach Shakespeare before he dies.

My extraordinary professor, Professor Anjum Nisar, has, in his wise life, reached points of life he must have thought about, and with Dilan Thomas' words as my guide, he says our words will not shine any brighter in our world. And in countries of dire straits like Yet, in countries close to the old man who compels them to set sail towards Byzantium - I am convinced the professor has finally reached him. Perhaps it was the reason his emotions bled into the recital when he taught us poetry, reflecting his beliefs in life mirrored in his relationship with literature, sometimes bordering on irony - his anger at the death of light.

As I write these lines, I am fascinated by the sense of transcendence shared strongly by Rainer Maria Rilke during a summer walk in the Vienna countryside, promoted as the Great Sigmund Freud. Freud later recalls wanting more lives in specific episodes of intimacy (and vowing sorrow as a reaction to death). However, Freud never understood Rilke's pain. Perhaps I never did either, but I could only feel what the poet felt. In all my rendezvous with the professor, I felt the same unbearable burden of responsibility for him. Perhaps I could not take his life as a chance encounter with mortality, but I always captured his image, recorded his voice, his life, and breathed life into the "perpetuity of art" as an antidote to the flight period in conversations with mortality. Keats' heart must have throbbed in his grand ode when he celebrated the temporary meeting of lovers in the shade of a tree. The evolution towards art, towards tranquility, towards perpetuity, immortalized only when sketched on bone, could save their temporary intimacy.

When a sophomore in 2018 came to teach John Donne and saved my heartbreak, his poetic magic saved my heartbreak. His words, fermented like old wine over years of "more life," reflecting the essence of literature as Harold Bloom does, were not unlike Keats flying with "unworn wings of poesy." His insights, his transversal implications, sometimes against Wallis Shah's Hyas and Homer's Odyssey - integrating the traditions of Orient and Occident, "filling me into fresh life," from Tagore's Gitanjali. Sometimes, when trying to teach a new semester, I feel compelled to think the professor is a man of dual lives. He sought hearts and passions to feel what the world cannot, and he felt it with us.

Recently, as I read Harold Bloom's memoirs possessed in memory, I continue to meditate on the literary company of old age. Bloom's book is a dissertation on his romance with literature at the end of his life. He recalls reading Shakespeare, Milton, Shelley, seeking refuge in them from sleepless nights and simple heartbreaks. I was immediately drawn into discussions with the professor. It was customary for my two friends, Zeeshan and Safdar, and I to visit the professor for almost every change of season. On an autumn evening at his place, as he was wise and attentive, Zeeshan asked him to talk about his latest romance with the literature of his gray years. He laughed. Oh, the way he laughed! A laugh attacked by his cough, an uneasy laugh. Comparing words in the air, he said, "I don't read literature much. But I read just to wet my tongue." As always, our response was a big "Wow!" Whatever he said, shared through deep contemplation as it took weeks to digest his words said with such prophetic ease, perhaps his reaction was a tribute to Eliot, who instructed poetry as poetry before revealing its true meaning. Hearing this, my simplicity strongly urged me to turn gray instantly just to become like him.

With his departure, I revisited lecture notes from his poetry lessons. I have a diary bound in leather from my undergraduate days that he taught us. I saved it for a lifetime. And why? I open it now before me. Something trembles within me. I cannot reconcile memory with awakening. Flipping through pages turned yellow with nostalgic anxiety, there he is! His heavy voice fills the room. The poet under discussion, most favored next to Yeats and Frost, is John Keats. The poem: Ode to a Nightingale. I remember writing the next line with religious reverence, not knowing how much I would need them more than ever before. The professor, touching upon the tragic in his voice, said these lines:

Songs have eternal value. The nightingale dies, but the song remains. How you depart from the world matters. You leave behind memories that continue to give life to others.

After that storm, there is a quiet silence, spreading everywhere.

In the two generations of his disciples, including many of my teachers, we must reflect on the questions the professor left us with. Like Keats, as we head towards the end of his prophecy, remaining charming to speculate on the vitality of the nightingale's song, we also share the eternal anguish of our beloved words, the professor of our love and the eternal bard:

"Was it a vision, or did I wake up?

The music that escaped: - Will I wake up?"