Recently, public opinion was stirred by the information that Nghe An recorded a case of diphtheria that did not survive. What is noteworthy is that the deceased had close contact with an 18-year-old girl in Bac Giang, who also tested positive. Immediately, health authorities traced and isolated those who had close contact with the girl; these individuals will have to be isolated until they receive two negative test results for the bacteria, and they will also be treated prophylactically with antibiotics for 7 days and monitored for health for 14 days from the last contact with the confirmed case.

Doesn't it sound like the COVID times? This is enough to show how serious the risk is, but I am sure many of us are still quite oblivious about this disease, perhaps only having heard about it in the combo vaccination for diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus. So today, let's learn about this disease.

The disease diphtheria

Diphtheria is precisely a troublesome disease that has plagued humanity since ancient times. In the 5th century BC, Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine and the creator of the Hippocratic oath that medical students must read before graduating, was the first to describe diphtheria. The first widespread diphtheria epidemic occurred in the 6th century AD. In history, diphtheria has been one of the most feared diseases in the world, with major epidemics occurring in the 1880s in Europe and the United States, with a mortality rate of up to 50% in some places.

The fight against this disease made significant progress in 1883 when the bacteria causing diphtheria was first found in diphtheria patients. A year later, the bacteria was successfully cultured, which laid the foundation for the discovery of the toxin produced by the diphtheria bacteria by the end of the 19th century, leading to the gradual development of the vaccine. In the 1920s, during World War I, the mortality rate in Europe dropped to about 15% thanks to the widespread use of diphtheria antitoxin. However, the diphtheria pandemic also ravaged Europe again during World War II. In 1943, there were 1 million reported cases and over 50,000 deaths.

Fortunately, with the advances in medicine in the 1940s, a vaccine based on diphtheria toxin was introduced in Europe and North America and quickly proved effective in reducing transmission in vaccinated communities. The vaccine gradually became more accessible and was used worldwide, but in the 1970s, there were still about 1 million cases of diphtheria each year, with 50,000 to 60,000 deaths in low- and middle-income countries. In 1974, the Expanded Program on Immunization was launched, in which the diphtheria vaccine was one of six vaccines used, resulting in a halving of the global diphtheria incidence rate.

From 1980 to 2000, the total number of cases decreased by over 90%, with the most recent major outbreak reported in the Russian Federation and the former Soviet Union in 1990. In the 8 years from 1990 to 1998, the disease spread to over 157,000 people and claimed the lives of 5,000. It can be said that even with the vaccine, the fight against diphtheria remains ongoing, especially in countries with low vaccination rates. It is estimated that about 86% of children worldwide are fully vaccinated with the recommended three doses of diphtheria vaccine, meaning that the remaining 14% have not or are not fully vaccinated. In temperate regions, the disease mainly occurs in the cold season, while in warmer regions, it silently spreads throughout the year.

From 2011 to 2015, India had the highest total number of cases each year, with 18,350 cases over the five years. Meanwhile, Southeast Asia was the source of most reported cases each year during this period. In Vietnam, the implementation of the diphtheria vaccine was included in the Expanded Immunization Program since 1984, with three basic doses for children under 1 year old. Additionally, in 2011, following WHO recommendations, Vietnam also implemented a booster vaccination with DPT4 for children 18 months old nationwide. Thanks to the success of the expanded immunization, the incidence of diphtheria continuously decreased from 84.4 per 100,000 population in 1984 to below 0.04 per 100,000 population in the years 2005 - 2010.

However, in recent years, diphtheria outbreaks have re-emerged in some localities, especially in the Central and Central Highlands regions, such as in Co Bang district, Gia Lai province in 2013 and 2014, and Dong Phu district, Binh Phuoc province in 2016. In the Central region, from 2015 to 2018, there were also diphtheria outbreaks with 28 cases and 7 deaths in several districts in Quang Nam and Quang Ngai provinces.

The emergence of diphtheria outbreaks in the community with a high mortality rate is a concerning public health issue in the locality and region. According to a report from the Pasteur Institute of Nha Trang in 2019, the Central region recorded 36 cases of diphtheria, with three deaths, mainly concentrated in Quang Nam and Quang Ngai provinces. Thus, you understand why diphtheria is a mandatory reportable infectious disease.

So what causes this disease?

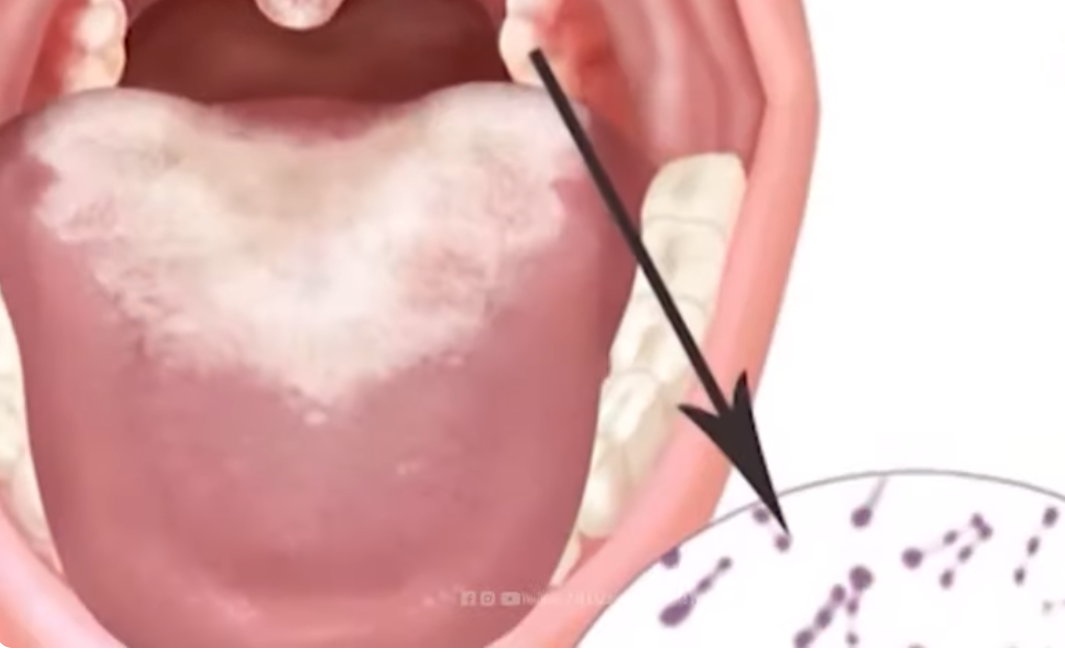

Unlike other common bacteria, this is a disease that is both infectious and toxic, and the serious damage caused by the disease is mainly due to the exotoxin of the diphtheria bacteria, scientifically named Corynebacterium diphtheriae. There are three forms of diphtheria: anterior nasal diphtheria, pharyngeal and tonsillar diphtheria, and finally laryngeal diphtheria.

In anterior nasal diphtheria, the infected person will have a runny nose with purulent mucus, sometimes with blood and a white membrane on the nasal septum; this type is usually mild because the bacterial toxin does not penetrate the blood much. Pharyngeal and tonsillar diphtheria are more dangerous, presenting with fatigue, sore throat, loss of appetite, mild fever, and after two to three days, a necrotic patch appears, forming a tough, white-greenish pseudomembrane that adheres firmly to the tonsils. It may also spread to cover the entire pharyngeal area; in some cases, there may be swelling in the submandibular area and swelling of the cervical lymph nodes, causing the neck to bulge out like a bull's neck. In severe toxic cases, the patient will be lethargic, pale, with a rapid pulse, and may become comatose.

If not treated aggressively, these individuals may not survive within 6 to 10 days. But that is not the most concerning type of diphtheria; laryngeal diphtheria is the form that progresses rapidly and is dangerous. The patient shows signs of mild fever, hoarseness, and cough, with pseudomembranes in the larynx or from the pharynx spreading downwards. If not treated promptly, the membranes can cause airway obstruction, leading to respiratory failure and rapid death. Besides the aforementioned locations, the bacteria can also cause disease in other areas.

In these cases, which are very rare and have mild progression, severe diphtheria cases are often associated with heart damage, most commonly myocarditis, arrhythmias, and may involve endocarditis and pericarditis. Additionally, diphtheria has neurological complications that often appear after a later period, such as bilateral facial paralysis, motor paralysis, or oculomotor paralysis, causing the patient to have strabismus. However, most neurological complications will fully recover within weeks to months, which is dangerous.

How is diphtheria transmitted?

Humans are the reservoir for diphtheria bacteria, and the disease is primarily transmitted through contact with infected individuals or asymptomatic carriers via respiratory secretions or through skin secretions containing diphtheria bacteria. This means that the disease is easily transmitted through the respiratory tract or through direct contact with secretions from the mucous membranes, nose, and throat of infected patients or asymptomatic carriers when they cough or sneeze, especially in densely populated areas or places with poor sanitation conditions.

The incubation period is usually from 2 to 5 days, but it can be longer; the period of disease transmission is often not fixed and can last about two weeks or shorter, at least over 4 weeks. Infected individuals can shed bacteria from the onset of symptoms or from the end of the incubation period, while asymptomatic carriers can shed the diphtheria bacteria for several days to three to four weeks. Therefore, in outbreak areas, asymptomatic carriers and those who have been in contact with confirmed cases need to be medically managed. Accordingly, those who have had close contact with patients must be tested for bacteria and monitored for 7 days, and should receive a dose of antibiotics or take prophylactic antibiotics for 7 to 10 days if they have been exposed to diphtheria, regardless of their immune status.

In cases where close contacts test positive for bacteria, they must be treated with antibiotics and temporarily refrain from attending school or food processing facilities until they receive negative test results. For those who have been vaccinated against diphtheria, a booster dose of diphtheria toxoid should be administered. In general, prevention is better than cure; children need to be vaccinated against diphtheria according to the full vaccination schedule. Simple preventive measures include regularly washing hands with soap, covering the mouth when coughing or sneezing, maintaining personal hygiene, and keeping the nose and throat clean. Daily, limit contact with sick individuals or those suspected of being sick, ensure a well-ventilated, clean space with adequate lighting, and there is no need to fear diphtheria at all.