One of the surprising aspects of the 2024 general election is that the Labour Party won a majority with a similar share of the vote as it lost in 2019.

Some on the left now seem to argue that the Labour Party can win this time with the same kind of leadership and policy platform it presented in 2019. This time, the view is that Labour's support is broad but shallow. In fact, there was an alternative path towards power with deep support. None of these views have materialized.

I understand the need to analyze the results of both 2019 and 2024. There are several reasons for Labour's low winning share. The key connecting many people is that the attitude of voters who did not vote for Labour is as important as those who give Labour a majority. Many people who did not vote for Labour in 2024 knew that their vote would not prevent a Labour victory. Some actively wanted that, but most would have been indifferent. However, unlike in 2019, they did not vote to try and stop it.

1) Labour's campaign was ruthlessly targeted. There was no wasted effort in getting votes in safe seats or in seats where the Lib Dems could beat the Tories. This would depress turnout in non-target seats.

2) Some previous Labour voters in safe seats voted for the Greens or various independents. Undoubtedly, this was a share of the vote for Labour. However, many of these votes were driven by the understanding that Labour had to win the election. In Vox Pop terms, they felt they were sending a message to Labour, or they felt liberated like a first preference in PR or the French first-round elections.

There is evidence for this. According to Ashcroft's election day poll, 61% of Green voters were captured in the last week at 31% a day. It is hard to describe it as anything other than shallow support. In contrast, 16% of Labour voters decided on the day.

3) Similarly, some Labour voters tactically voted for the Lib Dems. This not only effectively reduced the number of Tory MPs but also depressed Labour's share of the vote. Unlike in 2019, the Lib Dems primarily positioned themselves as an anti-Tory party. 46% of Lib Dem voters voted tactically ("I voted to stop my favorite party from winning"), while 50% voted positively ("I voted for the party I wanted to win the most"). Ashdown's survey.

4) Labour's changed political position made some Lib Dems feel they could tactically revert to Labour in seats where the Lib Dems could not win. They wanted to get rid of the Tories and felt comfortable with a Labour Prime Minister this time.

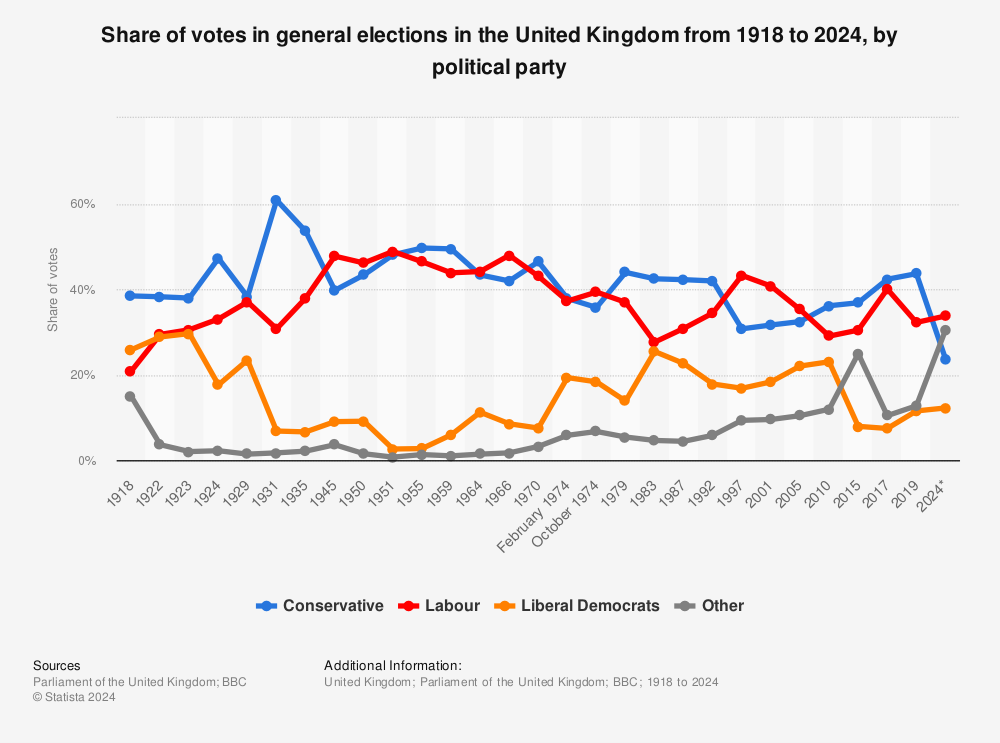

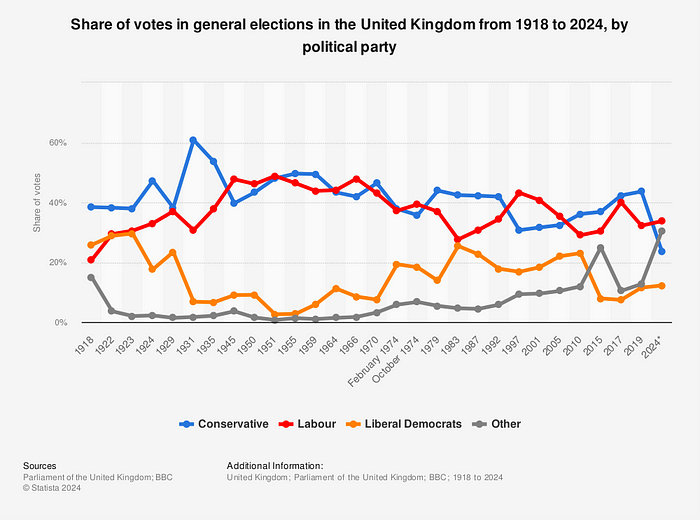

5) The share of votes going to the three main parties has decreased in the long term. This continued in 2024. However, 2017 and 2019 did not drop neatly as the graphic shows. The country appeared to have a two-party (SNP) system.

Two factors drove this. They occurred after a highly polarized and divided Brexit referendum. Jeremy Corbyn and Boris Johnson are the politicians driving the polarization. Both evoke strong feelings.

In 2019, the Brexit Party withdrew many candidates to encourage supporters to vote tactically against Labour. Previously, 25% of Labour-supporting Leave voters supported the Tories. A minority of voters passionately supported Labour, but the majority did not want a Labour government. Only 10% of YouGov poll respondents thought Jeremy Corbyn looked like a 'waiting Prime Minister' in 2019. In 2024, 40% thought the same of Keir Starmer. Tactical voting is generally thought of as an anti-Tory phenomenon, but it can also happen against Labour, and it clearly did in 2017 and 2019. Due to Labour's strategy and positioning, it was almost nonexistent in 2024.

6) In 2024, Reform gained five MPs, but their vote share was slightly more than the seats UKIP won in 2015. To keep Labour? A significant number of Labour's minority were in seats where Reform took a substantial number of previous Tory votes to become a three-way margin. Most Reform voters in those seats knew their vote would contribute to a Labour victory.

7) Undoubtedly, Labour's support is shallow. Disillusionment with politics and politicians is almost universal in the UK. But is Labour's support shallower than in 2019?

One hint is included in Ashcroft's poll. In 2024, 25% of Labour voters said it was slightly harder to decide how to vote in this election than usual. However, in 2019, that figure was 44%. For every Corbyn enthusiast who filled rallies or went to Glastonbury, there was another reluctant Labour voter. In 2019, at least some in Labour were convinced the party would lose.

8) There is another way to think about the shallowness of support. It may be an oversimplification, but the UK once had a uniform two-party system with class divisions, and there is truth in the idea that people are loyal to the party that benefits them economically or the party they inherited from their parents. Today, it is very different.

Whether you are socially liberal or conservative is no longer as important in determining voting preferences along the traditional economic left-right divide. People do not naturally divide into distinct groups in the new political environment, but over time, there tends to be a cluster of voters who consistently share common attitudes and values. John Curtice and Lovisa Moller Vallgarda ran the gold standard British Social Attitudes Survey using machine learning tools to identify six groups.

· Well-off traditionalists (12%)

· Political centrists (17%)

· Left-wing patriots (15%)

· Urban progressives (16%)

· Soft left liberals (14%)

Voting companies using different methodologies produced similar groups. The point is that the "people" often talked about by populists do not all agree or share the same interests. We have commonalities, but we do not agree on many things, and we do not divide neatly into two groups on the left and right.

The art and science of modern politics is about forming winning electoral coalitions from sufficient voters in these groups. Brexit may have forced this country to divide into two, but it is generally much messier. Parties that represent only one group in the way they speak to many remaining patriots may have passionate and even deep support, but that may not be enough to build a winning coalition in all but a few seats. A party that can have passionate rallies may be deep but narrow. Electoral success requires breadth, but it may not deliver a wider rally than the party's loyalists.

Boris Johnson said he reshaped British politics for the better, but even today, despite the right's enthusiasm, the permanent reshaping has turned to dust.

However, in an age where we can easily connect with like-minded individuals through social media, it is easy to think our individual views are actually more widely shared (especially when we are at rallies).

The first question for any campaign is

· What is your theory of change?

· How do you build broad support beyond the obvious base?

· How do you gain power?

· How do you neutralize the opposition?

The Labour Party answered these questions in 2024, but not in 2019.

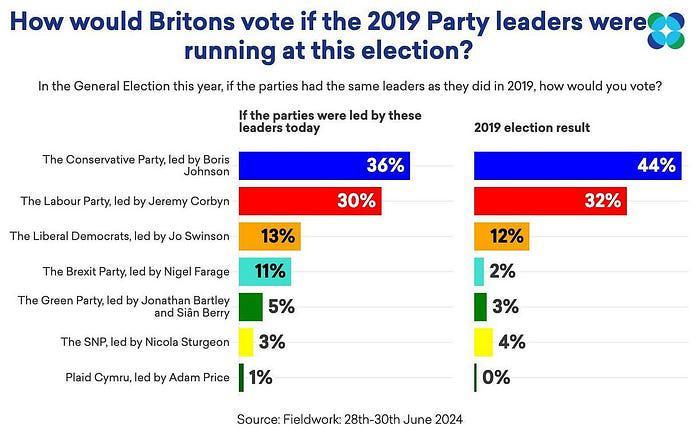

9) We have a slight indication of how the 2024 election would have played out with unchanged 2019 party leaders.

At the end of June, a poll asked how people would vote if leaders like Johnson, Corbyn, and Swinson were in charge in 2019. The Conservatives won over Labour 36% to 30%.

This could be the mother of all hypothetical questions and should not be taken too seriously, but it is still a surprising result at a time when Labour's poll lead was consistently over 20%.

Reasons Labour Won

The Labour Party achieved a significant victory because its strategy and leadership changed. It is wrong to claim that the similar share of polls from 2024 to 2019 means Labour would continue to progress regardless and still form a government.

Labour needed to broaden its support to effectively use votes to expand its backing among new groups of voters living in different parts of the country. And it had to present it in a way that prevented Labour voters from renewing it through tactical voting.

Of course, while recognizing the need for Labour's broad strategy, one may not agree with some of the choices along the way. Most will undoubtedly recognize that some mistakes were inevitably made.

Perhaps Labour overcompensated in some positions in 2019, but it may have been necessary to show real change. Voters do not always respond to nuance or even pay attention.

And those who argued that Labour's policy pledges were not surprising risk underestimating the damage to the country's economy and social fabric caused by a mix of austerity, Brexit, and incompetence over the past 14 years.

Voters have limited expectations of a new government, understanding how much difficulty the country is in and how hard it is to make immediate improvements. Liz Truss showed in just a few weeks that ignoring reality does not deliver what you expect. Voters want change, but they are skeptical about the mood Labour needs to capture and the prevailing mood. Better to have too few promotions than too many seats.

However, a winning electoral coalition inevitably becomes broad and somewhat shallow, but Labour was still exceptionally good at winning many seats. A minority of many are many, and initially, various parties challenge in second place. The Labour Party has to deal with challengers from the Greens and Reform as well as traditional Tory foes.

Electoral System

Finally - and on a tangent, there is a slight reflection on the electoral system here. The 2024 results appear very unfair. The Labour Party holds a majority with less than a third of the vote. However, the electoral system affects how people vote and how parties behave. The above people vote tactically or abstain in places where they will not change the outcome. But there are other, more subtle effects. The issue at risk in 2024 was whether a Labour government should replace the Conservatives. Many voted for other parties, but as a basis for being satisfied or at least indifferent to Labour forming a government. This makes a new Labour government as legitimate as any other.

Once you set all the criteria to design an electoral system, it quickly becomes clear that there is no perfect system that meets all or a single definition of making an electoral system fair. You may want every vote to count, make it hard for extremists, maintain constituency representation, and encourage a strong government with a few voters gaining total power. But no system can deliver all of this. Choices and trade-offs must be made.

I personally prefer change - the Jenkins Review would be fine with me. I have no certainty that this election will change the debate significantly. I have seen people argue about 2024 in two ways. The case for a changed system would be somewhat better at balancing advantages and disadvantages than the pre-post, but it does not solve all problems.