In the evening, the teacher would hide in the dark to catch men sneaking into the girls' dormitory. The boy in our class also liked to go to the girls' dormitory; he was quite cunning. After reaching the entrance of the girls' dormitory, he would feign a retreat and suddenly run back. Inexperienced teachers would think they had been exposed, believing that the student had discovered them, and would come out into the open. However, the teacher mentioned above, our homeroom teacher, was more cunning than this boy; he would stand in the dark, remaining still, and continue to wait. When the boy thought it was safe to return, the homeroom teacher would catch him.

There was also a math teacher named Guan Quehu, who was considered quite knowledgeable in the entire Tibetan region at that time. This teacher was proficient in both Tibetan and Chinese, and he was good at math; he was a versatile person, skilled in singing, playing instruments, and understanding physics and chemistry. He was a genius and later became one of the first master's degree students in the entire Tibetan region, specializing in ancient Tibetan language. Unfortunately, he passed away in his forties due to excessive drinking.

Teacher Guan Quehu was our middle school math teacher, and at that time, he was my arch-nemesis. The reason was that my math was very poor, and I didn't like math at all. So even during his classes, when he was writing on the blackboard, I would sneak out through the window to skip class. As a result, he often criticized me. Unexpectedly, after I graduated from vocational school in the early 1980s, I was assigned to my alma mater as a teacher, became a colleague, and eventually became the best of friends and drinking buddies.

Interestingly, at that time, our salaries were not enough to cover expenses; he didn't have enough, and I didn't have enough either. He knew an old man who owned a small shop, and he often went there when he ran out of money to write a note for credit.

The shop owner's surname was SHI, but I didn't know if it was the teacher's "shi" or the measure's "shi."

The note was written like this:

Old SHI: Give two bottles. Guan

Just a few words, Teacher Guan would hand the note to a student to go get the alcohol.

After I discovered this secret, I stopped the student who was on the way to the shop, traced it on paper, and kept a record of Teacher Guan's note. Then, following this note, I endlessly imitated it and racked up a huge debt at the small shop.

One day, when it was payday, Old Teacher Guan dragged me along to settle the bill. When settling the bill, the shop owner pulled out a pile of notes, and among them was his, but I had imitated his a bit more, and the total amount was quite large.

He was dumbfounded and said: I can't possibly owe this much.

The shop owner got angry and said: You, I kindly gave you credit, and you still deny it; you are too unreasonable.

I couldn't help but laugh at the scene, and Teacher Guan noticed that I had played a trick.

He said: You little rascal.

I can't remember how the accounts were settled that time, but thinking back now, I still find it amusing and can't help but laugh. In fact, Teacher Guan was also someone who loved to joke and play pranks.

In the mid-1980s, Old Guan, through his classmate who was an official working at Northwest Minzu University, had me take my salary to further my studies there. I studied for a year.

During my studies, I read a lot of Chinese novels and also wrote many Tibetan novels. At that time, a few of us published a Tibetan literary magazine called "Blue Moon." The most memorable work in this mimeographed publication was a photo novel titled "What Else Do We Have," which depicted a dialogue on a train between a person from the mainland and a Tibetan university student, where the mainlander asked the Tibetan student what they had there.

The Tibetan student replied, we have grasslands, cattle, and sheep.

The mainlander asked: What else?

The Tibetan student couldn't answer and muttered to himself: What else do we have?

That era was a time of questioning; many literary works were raising questions, and ours was no exception. The photo novel was a relatively novel approach at that time, and "What Else Do We Have" might have been the first photo novel in Tibetan.

Zhang Wan: That period was one of ideals.

Tsering Dondrub: In childhood, although I liked to draw, I had no concept of becoming a painter. If I had any ideals at that time, it was to be Chairman Mao's successor or perhaps a soldier.

By the time I was in middle school, my ideal was to be an official, to carry a good gun, and to ride a good horse, looking impressive. Later, in the late 1980s, I changed careers and left the teaching profession to become a judicial secretary, with a gun and a uniform. I really carried a gun, a short one. At that time, guns and uniforms were no longer fashionable; because I had naturally curly hair and long hair, wearing a wide-brimmed hat made me look quite comical.

As a child, I had a strong affection for guns. My father often repaired guns for others, and I liked it. After he fixed them, I would test fire a few shots. My father often asked me to try, and some people were quite generous, while others were reluctant to let me try those few bullets. Overall, I had more opportunities to handle guns than other children and understood their performance quite well; I knew a bit about several types of guns.

After graduating from high school, I wanted to be a writer. Near the end of high school, I wrote a novel called "Auspicious Marriage." Looking back now, it seems particularly naive, but at the time, it was a popular work and even won an award. This debut work was very encouraging for my future writing career.

Once writing became a habit, the ideal disappeared.

Zhang Wan: What changes have occurred on the grasslands?

Tsering Dondrub: In 1982, livestock was contracted, and in the early 1990s, after the grasslands were contracted, wild animals suddenly disappeared. In my childhood, there were herds of antelope, but now they are basically gone. At that time, there were bears, deer, cranes, and yellow sheep on the grasslands, but after 2010, those became animals of memory. There are still a few vultures. Wild rabbits and foxes still exist. Not to mention otters; even fish in the river are rare. The river's flow has decreased, and smaller rivers have dried up. Wetlands have disappeared. The grasslands have seriously degraded.

Now, winters have warmed; they are not as cold as in my childhood. Summers have less rain; in my childhood, it often poured heavily for several days in summer, but now it rarely rains. Our hometown is slightly better, but the rainfall is still pitifully low.

In my childhood, when living in a tent, heavy rain was quite annoying; water would flow on top of the tent, and water from outside would also flood into the tent. We often dug a small ditch around the tent, but when it rained heavily, the small ditch was useless. At night, the adults in the family would move things around in the tent to avoid rainwater coming from both above and the grass.

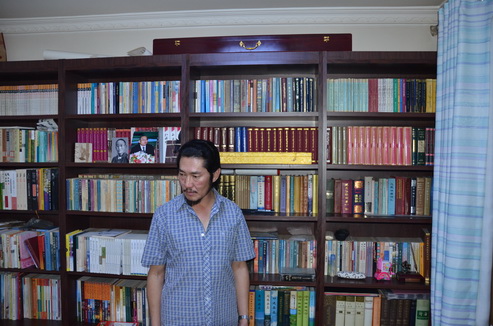

Tsering Dondrub was born in October 1961 in Henan County, Qinghai. From the age of 7 or 8 to 13, he herded at home, and from 13 to 21, he attended school. He has worked as a middle school teacher, judicial document writer, and historian. In 2013, he retired early to focus on literary creation. Since 1982, he has published over two million words of Tibetan and Chinese novels. Some of his novels have been translated into English, French, German, Japanese, Swedish, Dutch, Hungarian, and both old and new Mongolian, and have been included in textbooks for universities in Tibetan and Mongolian regions as well as some overseas universities. He has won numerous domestic and international literary awards.

ཚེ་རིང་དོན་གྲུབ་ནི1961ལོའི་ཟླ་བཅུ་བར་མཚོ་སྔོན་རྨ་ལྷོ་སོག་རྫོང་དུ་སྐྱེས། རང་ལོ་བདུན་བརྒྱད་ནས་བཅུ་གསུམ་བར་གནག་རྫི་བྱས། རང་ལོ་བཅུ་གསུམ་ནས་ཉེར་གཅིག་བར་སློབ་གྲྲིམས། སློབ་འབྲིང་དགེ་རྒན་དང་སྲིད་གཞུང་ལས་བྱེད། དེབ་ཐེར་སྒྲིག་འབྲི་སོགས་ཀྱི་ལས་ཀ་གཉེར་ཏེ2013ལོར་རྒན་ཡོལ་བྱས་ནས་ཆེད་དུ་གསར་རྩོམ་ལས་ལ་གཞོལ་བཞིན་ཡོད། 1983ལོ་ནས་ད་བར་དུ་བོད་རྒྱ་ཡིག་རིགས་གཉིས་ཀྱི་ལམ་ནས་བརྩམས་སྒྲུང་ཡིག་འབྲུ་ས་ཡ་གཉིས་ལྷག་སྤེལ། བརྩམས་ཆོས་ཁག་ཅིག་དབྱིན་ཇི། ཧྥ་རན་སི། འཇར་མན། འཇར་པན། སི་ཝེས་དན། ཧོ་ལན། ཧང་གྷ་རི། སོག་ཡིག་གསར་རྩོམ་སོགས་ཡིག་རིགས་དུ་མར་བསྒྱུར་ཡོད་པ་དང་བོད་སོག་སློབ་གྲྲིང་ཆེ་འབྲིང་དང་ནུབ་གླིང་གི་སློབ་ཆེན་ཁག་ཅིག་གི་བསླབ་དེབ་ཏུའང་བདམས་ཡོད་ལ། རྒྱལ་ཁབ་ཕྱི་ནང་གི་རྩོམ་རིག་བྱ་དགའ་ཐེངས་མང་ཐོབ་མྱོང་།