Denise feels hallucinations again and hears a voice calling her a failure to God, claiming that she will go to hell because of an abortion at 16. The voice of an unidentified man repeatedly calls her name, and she hears the sound of "cymbals clashing together."

Denise is my bipolar patient who has psychotic episodes, experiencing auditory hallucinations and paranoid delusions, convinced that her 98-year-old neighbor is breaking into her home to steal her medication.

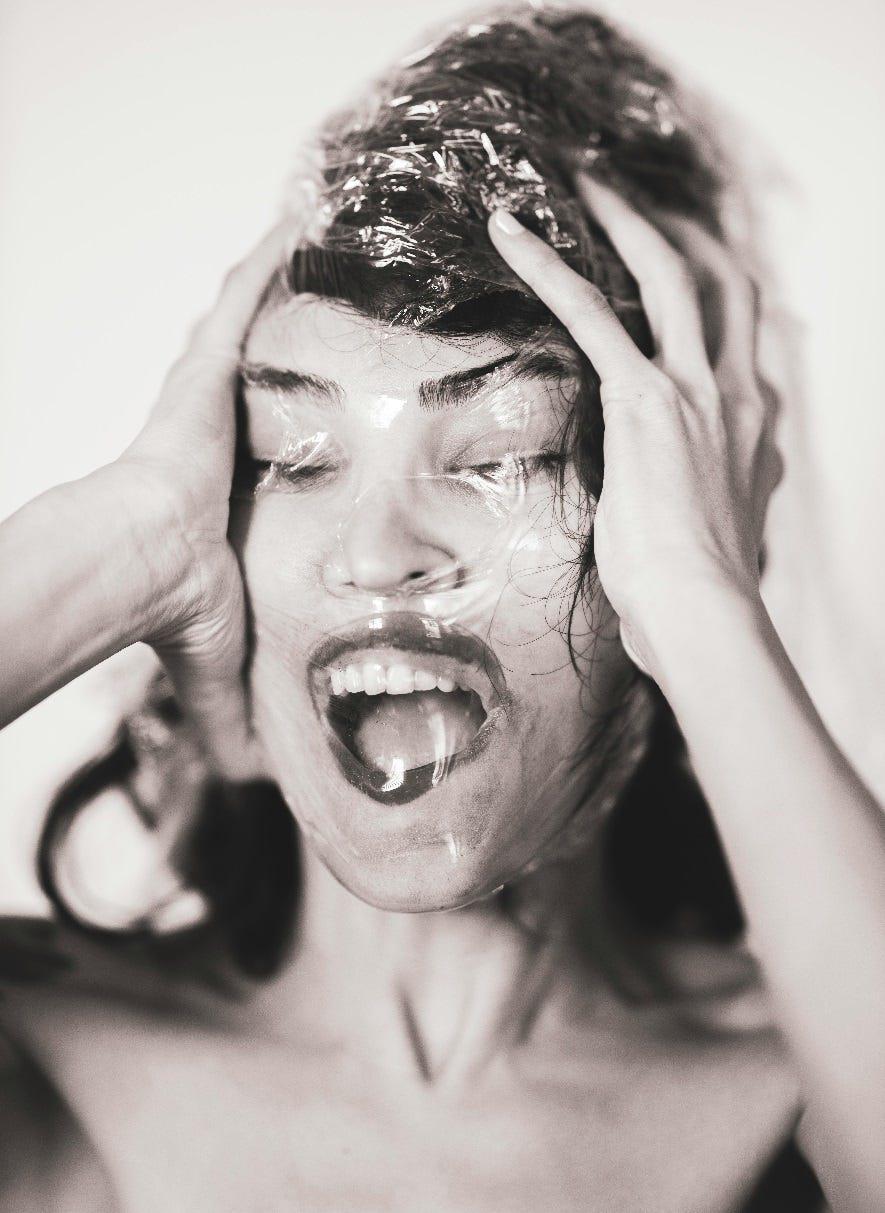

She has visions of dead family members wrapped in snakes and worries that aliens are communicating with her through her microwave. She has not slept more than three hours a week and has no appetite. Above all, she is concerned about doing something irreversibly crazy.

Crazy has a clinical definition. Unstable mood, poor judgment, lack of insight. Aggressive behavior, confusion, hostile influences. Auditory hallucinations, persecutory delusions, threatening behavior. I can think about these things and document them, but I cannot tell Denise these things while she is in the midst of a psychotic episode. What I tell her is no. You are crazy. You are crazy because you came to me asking for medication and help, and crazy people don’t do that.

What I can do for the troubled individual is harsh compared to the constellation of services they truly need, but the assurance that the structure of reality has not been canceled, that they are bound to the earth they know, and that their minds remain intact is one of the important things. Next comes medication and finally hospitalization.

Because crazy is our common language, we will not stop using “crazy.” We know what it means if someone is crazy or mad or insane. We undoubtedly know people who have been crazy. We know someone who lives in the bushes in front of a 7-11 and has vivid conversations with themselves. We also know that you hear from medical professionals that you are crazy. I hope for you because I see you and you haven’t gone over the edge. Crazy people do not know they are crazy because they no longer have a reality to compare themselves to. Today, while driving to the grocery store, I saw a man tying a teddy bear to a sign that read “active CIA recruitment.” That man does not think he is crazy.

Shorthand language tends to be fast and dirty. There is never enough time to explain, so we use universally understood, undeniable, and unfriendly terms. “Where is your mind?” asked the police officer who arrived at the scene after I called 911 about a murder.

Addict. Psycho. Loonie tune. Like crazy, these words are used in haste but are not always hateful. They denote urgency and vision. Being an addict or a psycho points out that one is currently acting like an addict or a lunatic. Whether it’s a moment or an episode, when one goes crazy, it communicates to me that not everything is okay, that my help is just what is needed. Leaving a message at my clinic saying you went crazy is very different from having a hard time or feeling bad.

According to clinical literature, we should not use “crazy” because it is stigmatizing. It forces the notion that all people with mental illness are “crazy” or act in violent or irrational ways. Robert Spencer mentions in a part of the NAMI blog that crazy is used thoughtlessly, but he does not agree.

The crazy are sacred. Crazy is a message, but it is not the whole language. It is a symptom, but it is not the whole disease. If you have been there, you know it can come back, and if you have come back, you know the fear of hell that can always be with you.

Let this fear remind you of the kind of resilience needed to heal a broken mind. Let this anxiety remind you that you lived to come back from the place of madness and to tell the story.