Investing in Stocks

These public companies have contributed to building a solid middle class in America, and for those who understand how the market operates, trading stocks can become a pathway to wealth. A typical example is the story of Warren Buffett, a humble man with a passion for folk music but a billionaire investor, a towering figure on Wall Street, and the most famous investor in America with a massive fortune of over $130 billion by 2024.

Buffett is known for his unique value investing philosophy. He focuses on meticulously analyzing companies, carefully considering their balance sheets and business operations. However, he also offers simple advice for those who don't have much time: buy low-cost index funds that mimic the S&P 500. This type of fund allocates the smallest investment amount to all companies in the index, allowing you to participate in the overall growth of the stock market. This is an alternative to entrusting your money to professional investors who often charge high fees with the promise of beating the market, which is often hard to achieve. Buffett himself once bet $1 million that an index fund would outperform a hedge fund over ten years, and he won.

Choosing stocks is a game full of risks, but there is a popular strategy based on the theory of John Maynard Keynes, one of the greatest economists of the 20th century. According to Keynes, in the stock market, the true value of a company is not always accurately reflected in its stock price. Instead, it is the popular story that people believe about the company that is the determining factor; sometimes this story is based on reality, as in the case of Chipotle's stock plummeting after a series of food poisoning incidents, or the Volkswagen emissions scandal that caused the company's stock to crash, but often the story is just hype. In the 1990s, internet companies emerged as the most attractive investments, driving market values to dizzying heights.

The popular story at that time was that internet companies would dominate the world and that focusing on profits was unnecessary. While this story was somewhat true with the success of giants like Amazon and Google, the problem was that no one could predict the level of market growth, whether it was a bubble about to burst or not. The hype surrounding internet companies created a domino effect that pushed stock prices to absurd levels, like a snowball rolling downhill, and the bubble eventually burst, ending the internet market's golden age. The bubble burst, leaving severe consequences: 300,000 jobs in the tech sector suddenly vanished, the U.S. stock market plummeted at an unprecedented rate, shocking investors, but this recession did not only affect investors; it also dragged the economy down, putting millions at risk of losing their jobs, with companies going bankrupt and pension funds being depleted.

Naturally, even when the stock market is thriving and investors are profiting, the economy can still suffer. A typical example is the most severe energy crisis since World War II. In 1973, Americans had to line up early in the morning hoping to buy enough gas for the day. Widespread instability and rising prices made people angry and anxious about the future of the U.S. economy. In that context, questions began to arise about how large corporations operated. Milton Friedman, a famous economist, provided an explanation for this phenomenon. He argued that greed is the driving force of every society, and businesses are no exception.

In 1970, Friedman published a shocking essay in the New York Times, arguing that because corporations are owned by shareholders, their sole mission is to generate profits. Corporations followed Friedman's advice, tying executive pay to stock performance. This meant that CEOs would do everything possible to increase stock prices, even at the expense of employees, customers, society, the environment, or even the company itself in the long run. They focused on short-term solutions like cutting costs or buying back shares to create artificial price increases.

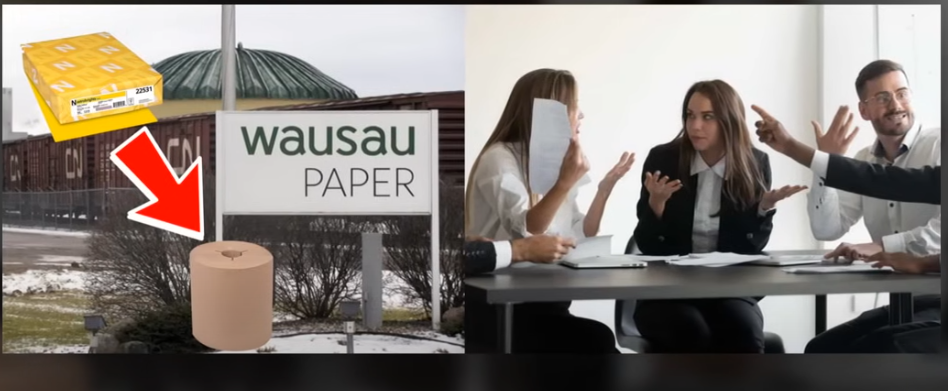

From 2007 to 2016, companies in the S&P 500 index spent more than half of their earnings in this way, with the remaining 39% paid to shareholders as dividends. As a result, very few resources were allocated for raising wages, expanding operations, or developing new products, which are crucial for the sustainable growth of the economy. The story of Wausau Paper in 2012 is a clear example when the company was investing in transitioning from printing paper to tissue paper; an investment fund bought a large amount of stock and pressured the company to cut costs and increase dividends instead of continuing long-term investments.

Ultimately, Wausau Paper had to close its Brockcomil plant, resulting in 450 people losing their jobs. This news was not only a shock to the workers who lost their livelihoods but also dealt a heavy blow to the Procore community, where the company had taken root from the beginning. Today, companies are increasingly focused on short-term shareholder interests, neglecting their long-term responsibilities to stakeholders. This trend has been around for a long time and is becoming more common and alarming. It seriously threatens the ability to pursue sustainable projects that lay the foundation for the long-term economic development of businesses.

Each Share is Like a Vote

In 1973, a CEO in America earned an average of 22 times more than a regular worker. By 2016, this figure had risen to 271 times, and as the stock market continued to expand, the number of Americans benefiting from that growth decreased. The percentage of Americans investing in the stock market is at its lowest level in 20 years, as the middle class gradually withdraws. Therefore, it is no surprise that rising stock prices in America coincide with increasing inequality, but things do not necessarily have to unfold this way. The stock market is a place that allows people to decide which companies deserve to succeed and which ideas are worth investing in.

Looking on the bright side, shareholders can influence how businesses operate, shaping the interests they care about. Most of us are oriented towards the long term; we have our own moral values and wish for companies to make money by creating things that are beneficial to the world, not by harming and destroying the lives of others. That is what shareholders truly desire, and we can absolutely become such shareholders.