TL; DR: My old company, Smallhold, raised a lot of money by branding itself as a technology company justifying a mushroom farm. We built a very popular mushroom company and brand, but we were unable to make critical decisions at crucial moments to sustain the business. This led to a minority investor taking control, and in my opinion, poorly executed cuts occurred. We might have taken a slower, more sustainable growth path, but we chose the fast lane.

Almost six months ago, I resigned in protest from Smallhold, the company I co-founded with my (now) best friend seven years ago. Today, it is emerging from Chapter 11 bankruptcy as a shadow of the company we once envisioned. The new owners, a private capital group, were making unfortunate investments in the struggling mushroom farm company. Some of their restructuring decisions were expected and even necessary, but others were not, and they ran counter to the principles on which we built the company.

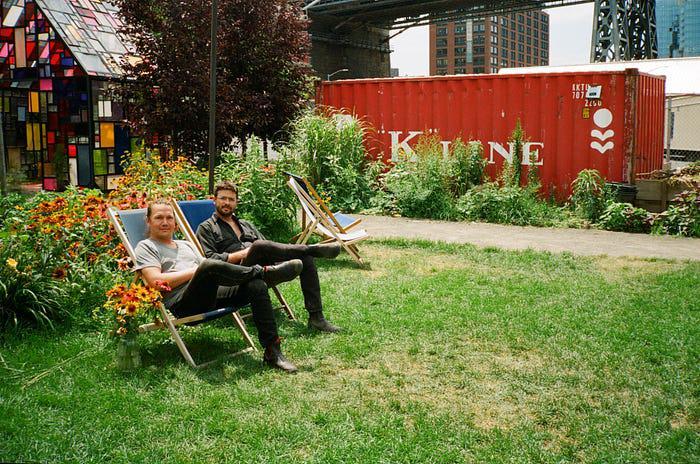

Along with my co-founder and a team of over 100 passionate farmers, operations team members, technicians, salespeople, and marketers, we created a new category of specialty mushrooms at the national retail level. We produced the first organic farm in NYC from a 20-foot shipping container under the Brooklyn Bridge, producing 100 pounds to date and about 40,000 pounds of mushrooms weekly across three cities nationwide. We also became a focal point during the COVID mushroom era, featured in all major national news outlets, and produced hundreds of thousands of pounds of organic mushroom compost for farms and gardens across the country. At its peak, Smallhold generated about $17 million in annual revenue (up from just a few hundred thousand a few years prior), with a post-money valuation of about $90 million, supported by $58 million in angel investors, institutional VCs, and debt. We sold to Whole Foods nationally, as well as eRewhon, Sprouts, and many other retailers. It’s safe to say we created gourmet specialty mushrooms like oyster and lion's mane.

However, we never made a profit and lost over a dollar on every package we sold.

A little background on specialty mushrooms: These include fungi such as shiitake, lion's mane, oyster, and king trumpet. For the past century, U.S. grocery stores have stocked only white button mushrooms, primarily grown and sold by a few large corporations. However, specialty mushrooms have a short shelf life and require different growing, shipping, and merchandising conditions. Smallhold launched seven new products simultaneously while building the necessary supply chain and agricultural infrastructure on a national scale within three years. It was a refreshing journey... but we spent a tremendous amount of money.

Since resigning on Valentine's Day 2024, I have been able to talk to many former team members, vendors, producers, and other farmers at various stages of creating my own mushroom farm and related businesses. Smallhold created significant value by shipping millions of pounds of waste-neutral organic produce (much of which was used to offset American meat consumption), but when the new owners went bankrupt shortly after I left, it left a significant hole.

At first, I was cooperative when the new investors acquired a majority stake and took control of the company. We desperately needed someone to push the team to make the tough but essential decisions that management had avoided for too long. We already had a well-developed plan approved by HR and legal to reorganize and streamline the business. This included allocating about $500,000 for severance and PTO for a team of 100. The budget was modest, but it was fully prepared and explained at the bank. Our approach was clear. We were burning about $1 million a month, or $250k a week. The plan, with about six months of foresight, was to reduce the workforce, cut unnecessary tech costs, close a half-empty 36,000 square foot farm in LA, and reduce headquarters costs by $30,000/month while elevating the company to a special type of Chapter 11 bankruptcy designed specifically to support small businesses (Subchapter 5). By acting quickly and efficiently, we could treat the team fairly using newly neutralized burn of $500,000 over two weeks. This last part did not happen.

The entire team was acutely aware that Smallhold's path was untenable. We had weekly meetings with both leadership and the board for months. We had tightened budget constraints for two years, but there were no signs of relief. Even though we were involved in management decisions, it was clear to everyone that action was necessary. Yet, no one came. Still, we were setting up interviews for shining segments in major outlets like Martha Stewart Living and NPR's Marketplace that were not wrong.

Eventually, our crew learned about the changes, but there was no official announcement. Instead, one day, the LA farm team's work simply did not arrive. It was a mess.

For two years, I had been advocating for new management at Smallhold. In 2021, I stepped away from my role as COO to make way for an operations professional with national logistics and construction experience. However, the company continued to promise technology returns on mushroom farm margins and pushed forward. Now, we were facing the consequences that most of us had seen coming.

When the new owners brought in new management, it was naturally someone they knew well. However, it soon became clear that they did not understand our values, let alone the business itself. They appointed a former COO of Burger King Brazil as interim CEO and a restructuring officer as CFO.

The new team adopted a Chapter 11 Subchapter 5 bankruptcy plan but decided to eliminate $500,000 in severance and PTO. They believe they are acting for the maximum benefit of the investment, but I strongly feel that this decision, along with the early interim appointment of a fast-food executive, did not align with Smallhold's core values as a sustainable agricultural brand. This approach contradicted the principles of sustainable B Corps that have always advocated for regenerative agriculture and living wage jobs. Closing all our farms, replacing high-quality mushrooms in packaging with lower-quality produce without notifying consumers, and denying farmers almost any rejection and pay time was objectively damaging to the brand's integrity and mission.

Of course, my team and I are not exempt from responsibility. Our senior management and board were unable to make critical decisions at crucial moments. Our inability to act frequently paralyzed us for two years and caused a massive amount of internal stress. Often, cuts made by the new owners were necessary due to insufficient information. We had to recognize much sooner that we were not a "technology" company, especially after a complete capital raise and valuation reset to $20 million. Ultimately, it was painfully clear to everyone what was necessary to accept reality: we were a mushroom farm.

I understand why it is difficult to break this mindset. My co-founder and I, both ambitious futurists, were determined to create sustainable food alternatives for a climate-derived future. We bet our careers on the (correct) assumption that the specialty mushroom market was huge, and we wanted to be a dominant national brand (and we were). This should have been enough to wet investors' whistles. However, for a nascent produce category with little infrastructure, this also meant significant construction and capital expenditures.

We believed that if we could expand quickly enough, we could gain market share and promote market expansion through consumer education of new fungi on Whole Foods shelves, building farms in major cities nationwide. It was true, but there were no profit margins. All that technology and infrastructure unsettled us and complicated things. Classic, really.

As a VC-backed company, you either accept that you need to dominate the market and set your own margins (like Uber) or compete on price (like everyone else). When the latter happens, reality sets in. In this sense, Smallhold's story resembles many other VC-backed startups in the agricultural space in recent years. Money ran out, and the economics of our unit were weak due to all the bloat, and we were born as the last horse in the investor portfolio finish line. If we had acknowledged earlier that Smallhold was not a technology company, we might have survived with some cash and a way out of the rut. But now, as a fellow of another defunct vertical farm, I once told a room full of my colleagues.

"Technology cannot be eaten."

Our story diverged from the typical startup crash trajectory in one significant way. The waste stream of Smallhold was inherently good for the planet. The byproduct of growing mushrooms, typically seen in dead wood, is organic compost. And the trimmings from our mushroom packing line were actually valuable healthy mushroom bits that could easily be used in many other products. Our team made a living, and the packaging was compostable. The company platformed environmental artists, avoided traditional advertising strategies, and relied on our B-CORP to drive sales and educate consumers.

After 18 years of accelerated education in business strategy, mycology, capital expansion, agriculture, and entrepreneurship, I realized that some things should not be exposed to speculative investment and debt. This is the truth I learned over about five years on the rocket ship trajectory of Smallhold, and I now share it with you.

Food, especially good, healthy, environmentally friendly, circular economy food, must be, at least in part, sacred.

Yes, I know this is how "you play the VC game." Since graduating from college, I have played it, flying from one startup to the next with varying degrees of success. At Smallhold, I truly believed we could give VC a "jagged little pill" that could change its trajectory toward platform regenerative agriculture. And we were mostly wrong.

We failed. The VC bet failed because it is inherently speculative. If you want to ride that dragon, you literally have to be a dragon rider. I could not ride the VC dragon. Neither could my co-founder. At least not in that way. And that’s okay. As you know, we absolutely need to drive innovation, and venture capital is a powerful tool in the right market. However, when the bust cycle hits - which is always more extreme in VC - the people who suffer the most are often the most important:

- Farm workers are being laid off by distant investors trying to salvage investment profits.

- Consumers are left with higher access to healthy foods like organic mushrooms at lower prices. Smallhold fills clamshells with mushrooms shipped too far to keep fresh.

- Agricultural entrepreneurs inspired by Smallhold are left with debt, scrambling for new customers, and justifying their work to investors.

- Third parties that supplied Smallhold continue to suffer after bankruptcy (despite not receiving payment for delivered products) and are hit financially. Many of them are farmers as well.

So, with that in mind, what if we reset expectations for "impact" investing in agriculture?

Some thoughts:

- Founders: Don’t deceive yourself. If you want to create lasting change for the better in this world, aka "make your dent" in a climate or health-positive way - the most statistically viable path for you is slow and steady. Sure, it will be overhyped. But don’t pull the wool over your own eyes. When you sign a term sheet, it’s a promise - even if it’s a crazy one. If it’s promised that a sustainable agriculture business model will yield 10x returns, ask yourself if you can hold onto it. Surely you can. If the answer seems to be "yes," you can call me first.

- VC associates and analysts: If you actually want to do "good" in this world, push companies to include other metrics in evaluating agricultural and farm technology. Learn how agriculture actually works. Seriously, learn how crop cycles work, how growing conditions affect density and yield, and dig deep into the economics of specific commodities. If someone promised you that they will technically grow lettuce with 10x returns in five years - tied to diesel prices and grown cheaply in places like Mexico - take a step back and ask yourself, "What?"

- Partners: Don’t expect SaaS to come back from founders of specialty crops or commodity crops! Yes, even if industrial robots are tending to the crops. If you need larger, more predictable returns, there are plenty of great ag tech companies that can provide John Deere, Kubota, and Trimble. However, if you want to invest in sustainability, you need to set expectations around the fact that most markets are not actively encouraged to support new sustainability standards at an early stage of the adoption curve.

- GPS: Question your ethics. If you are in this for the money, great. You can still call yourself "impact," but what are you impacting? How? Have you talked to them? What do they need to support growth beyond money? You can still be ethical and make money. You don’t have to invest in agriculture! If you do, know that it’s a volume business filled with difficult externalities.

- LPS: You have ultimate power. You must hold your portfolio funds accountable to your investment strategy. However, at the end of the day, if you are supporting impact investment funds that invest in agriculture, you must hold them fully accountable. Ensure that goals are met and that those goals are supported in how new deals are constructed. Push for triple bottom line accountability. In a world of concentrated wealth, we need you and your colleagues to push us in the right direction. Invest in founders and companies that provide sane returns in this space. And if you want larger returns, perhaps look somewhere else and be honest about it.

If you want to make a real change with impact investing, you need to collectively redefine the concept of "returns" to include true triple bottom lines, meaning expectations for people, planet, and profit.

Deeply reflected in the spreadsheets from Smallhold's bankruptcy and clearly reflected, if we had aligned expectations around these three pillars, I think we would have succeeded in all of them. Instead, we played the only game we thought we could compete with large agriculture. In doing so, we all lost something real and valuable for the world.