The Rise of Nabopolassar and the Fall of Assyria

Before the arrival of the Parthian and Sasanian periods, reflecting on a key turning point in Mesopotamian history—the rise of Nabopolassar—helps us understand the power transitions and cultural changes in this land. Nabopolassar (reigned circa 658 BC – 605 BC) was the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, and his story begins on the fringes of the Chaldean tribes, filled with rebellion and opportunity.

The Chaldeans were a nomadic tribe living in the marshy regions of southern Mesopotamia, long oppressed by the Assyrian Empire. The Assyrian Empire was known for its military expansion and harsh rule, but by the late 7th century BC, internal corruption, overexpansion, and external pressures had put its hegemony in jeopardy. Nabopolassar keenly seized this opportunity. He did not come from a prominent background, but through political acumen and military talent, he gradually established prestige among the Chaldeans. His rise was not instantaneous; rather, it was achieved by uniting other forces dissatisfied with Assyrian rule, gradually undermining the foundations of this vast empire.

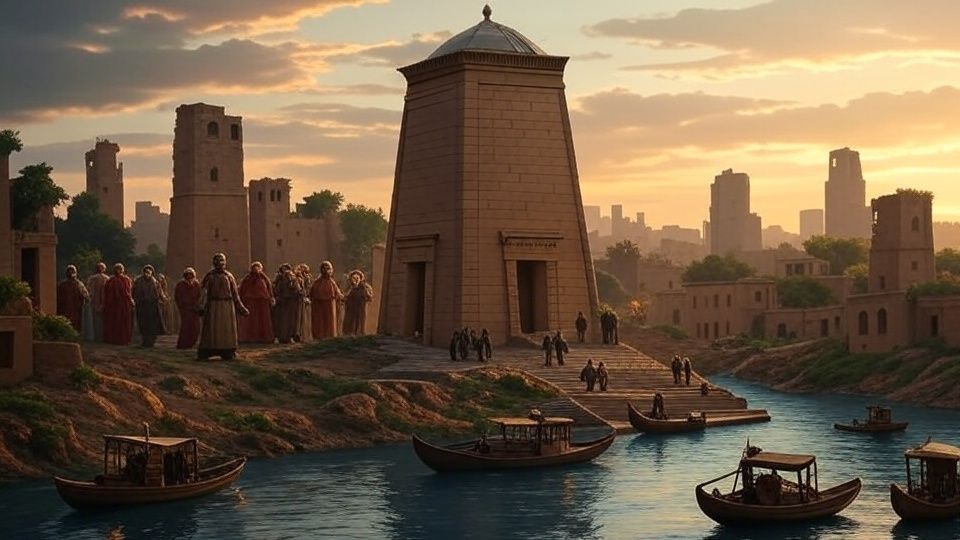

A critical turning point occurred in 626 BC when Nabopolassar declared himself king of Babylon, openly challenging Assyrian authority. He allied with the Medes, an emerging Iranian tribe, forming a powerful anti-Assyrian coalition. The Medes were skilled in mountain warfare, while the Chaldeans were familiar with the plains and rivers of Mesopotamia, making it difficult for the Assyrians to withstand this combined force. In 612 BC, the coalition captured the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, a city that symbolized Assyrian hegemony, which was completely destroyed, marking the end of the Assyrian Empire. Nabopolassar then consolidated the rule of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, rebuilding the city of Babylon and briefly restoring its former glory.

Nabopolassar's success was not only a military victory but also a revival of Mesopotamian political and cultural traditions. He renovated Babylon's religious centers, such as the temple of Marduk, in an attempt to restore the glory of Sumerian-Babylonian culture. However, his empire failed to maintain this momentum of revival for long, as the course of history would soon lead Mesopotamia into a new chapter—the rule of the Persians, Parthians, and Sasanians.

The Parthian Empire: A Transitional Period for Mesopotamia

The rise of the Parthian Empire marked the beginning of a new historical phase for Mesopotamia. The Parthians originated from nomadic tribes in the northeastern Iranian plateau, and by 141 BC, the dynasty established by Parthian king Arsaces I gradually came to control Mesopotamia. Under Parthian rule, this land gradually lost its independent status as a center of civilization; Babylon was no longer the political and cultural core but became a frontier zone contested between the Parthian Empire and the Roman Empire.

The Parthians governed Mesopotamia with a strong pragmatic approach. They retained the local administrative systems, such as the provincial system and tax structures of Babylon, which were inherited from the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Babylon's writing traditions, such as cuneiform, continued to be used for local records and religious documents, but their usage gradually diminished as Greek and Parthian began to dominate. This linguistic shift reflected a cultural fusion: the Sumerian-Babylonian traditions were gradually permeated by Hellenistic and Iranian elements.

In terms of religion, the Parthian Empire exhibited a high degree of tolerance towards Mesopotamian traditions. The worship of traditional deities like Marduk continued, but the Parthians introduced elements of Zoroastrianism, such as the worship of the god of light, Ahura Mazda. This religious fusion allowed Mesopotamian religious centers, such as the Esagila temple in Babylon, to retain some influence, but their status was no longer what it once was. Additionally, the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon rose as a new political and cultural center, further marginalizing Babylon's position.

Parthian art and architecture also reflected this cultural amalgamation. The Mesopotamian brick construction techniques were inherited by the Parthians, but their palace and temple designs incorporated the colonnade styles and decorative patterns of the Iranian plateau. This mixed style not only preserved the architectural heritage of Mesopotamia but also infused it with new vitality. However, with the frequent wars between the Parthians and Romans, Mesopotamia became a battlefield, and cities and cultural heritage suffered destruction, further exacerbating Babylon's decline.

The Sasanian Empire: The Persianization of Mesopotamia

In 224 AD, the Sasanian dynasty overthrew the Parthians, establishing a more centralized empire. The Sasanian Empire centered on Iranian culture, attempting to revive the glory of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. During this period, the Sumerian-Babylonian culture of Mesopotamia was further absorbed by Persian traditions, and Babylon completely became a province of the empire.

Sasanian rulers, such as Ardashir I and Shapur II, established Zoroastrianism as the state religion, which had a profound impact on Mesopotamian religious traditions. The worship of traditional deities like Marduk gradually became marginalized, and Zoroastrian temples and fire altars were built throughout Mesopotamia. However, the Sasanians maintained a relatively high degree of tolerance towards local religions, allowing Christianity, Judaism, and traditional Mesopotamian religions to coexist to some extent. For example, the Jewish community in Babylon compiled the Babylonian Talmud during this period, becoming an important text in Judaism and showcasing the diversity of Mesopotamian culture.

In terms of administration and economy, the Sasanian Empire inherited and improved upon the Parthian system. They implemented a more efficient tax and irrigation system in Mesopotamia, with techniques traceable to the Sumerian-Babylonian period. Agricultural productivity in the Tigris-Euphrates basin reached new heights during the Sasanian period, with Ctesiphon becoming the heart of the empire, connecting trade networks between East and West. However, Babylon's role as a cultural center nearly disappeared, with its glorious past surviving only in literature and ruins.

Sasanian art and culture further deepened the trend of Persianization. Their reliefs, silverware, and textiles blended Mesopotamian patterns with Persian styles. For instance, Mesopotamian-style lions and bulls frequently appeared in Sasanian palace murals, but these motifs were reinterpreted as symbols of Zoroastrianism. This cultural fusion was both a continuation of the Mesopotamian heritage and a dilution of its uniqueness.

The Continuation and Dilution of Mesopotamian Heritage

The rule of the Parthian and Sasanian empires in Mesopotamia both continued the Sumerian-Babylonian heritage and inadvertently pushed it towards marginalization. In terms of continuity, both empires preserved Mesopotamian administrative, agricultural, and architectural techniques. For example, the irrigation systems invented by the Sumerians were further developed during the Parthian and Sasanian periods, ensuring agricultural prosperity in the Tigris-Euphrates basin. Religious traditions were also preserved to some extent, especially during the Parthian period, when the worship of local deities still existed.

However, the trend of dilution was more pronounced. With the deepening of Hellenization and Persianization, the language, script, and religion of Babylon gradually lost their dominant status. Cuneiform was replaced by Greek, Parthian, and Persian, and the influence of the Marduk temple was overshadowed by the Zoroastrian center in Ctesiphon. Babylon's status as a political and cultural center was completely stripped away, and Mesopotamia became an ordinary province within the empire's territory.

This dual process of continuation and dilution reflects the changing role of Mesopotamia within the broader Iranian and Persian cultures. The Sumerian-Babylonian heritage did not completely disappear but was integrated into the cultures of the Parthians and Sasanians in new forms. This fusion was both an inevitability of history and a testament to the resilience of Mesopotamian civilization.

The Mesopotamia of the Parthian and Sasanian periods is a story of moving from glory to marginalization. The rise of Nabopolassar brought a brief revival to this land, but the rule of the Parthians and Sasanians gradually blended Babylon's glory into the grand narrative of Persia and Iran. The cultural heritage of Sumerian-Babylon continued on a new historical stage, but its unique brilliance was no longer as dazzling. The fate of this land, like the waters of the two rivers, constantly seeks a new home amid change.