Fatty liver is not just caused by eating too much fat

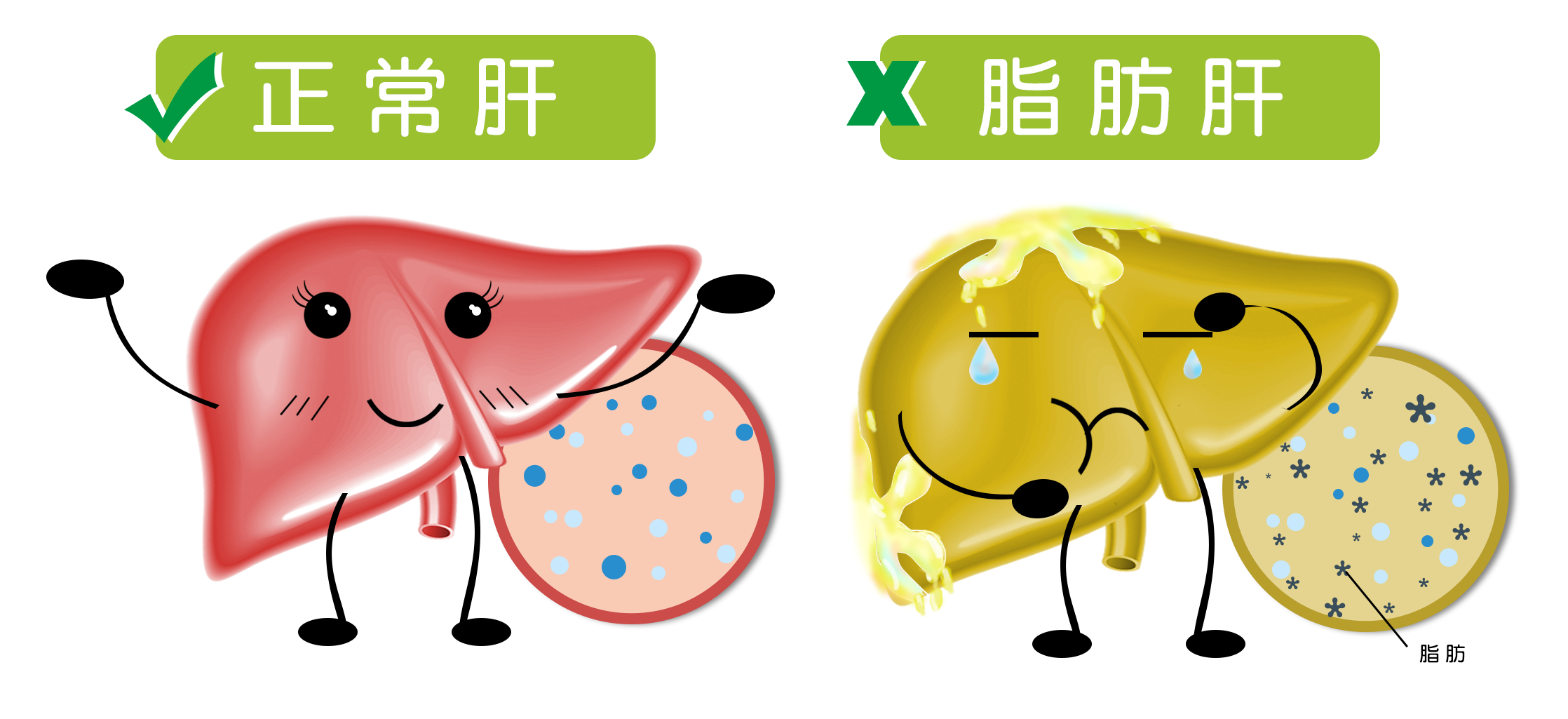

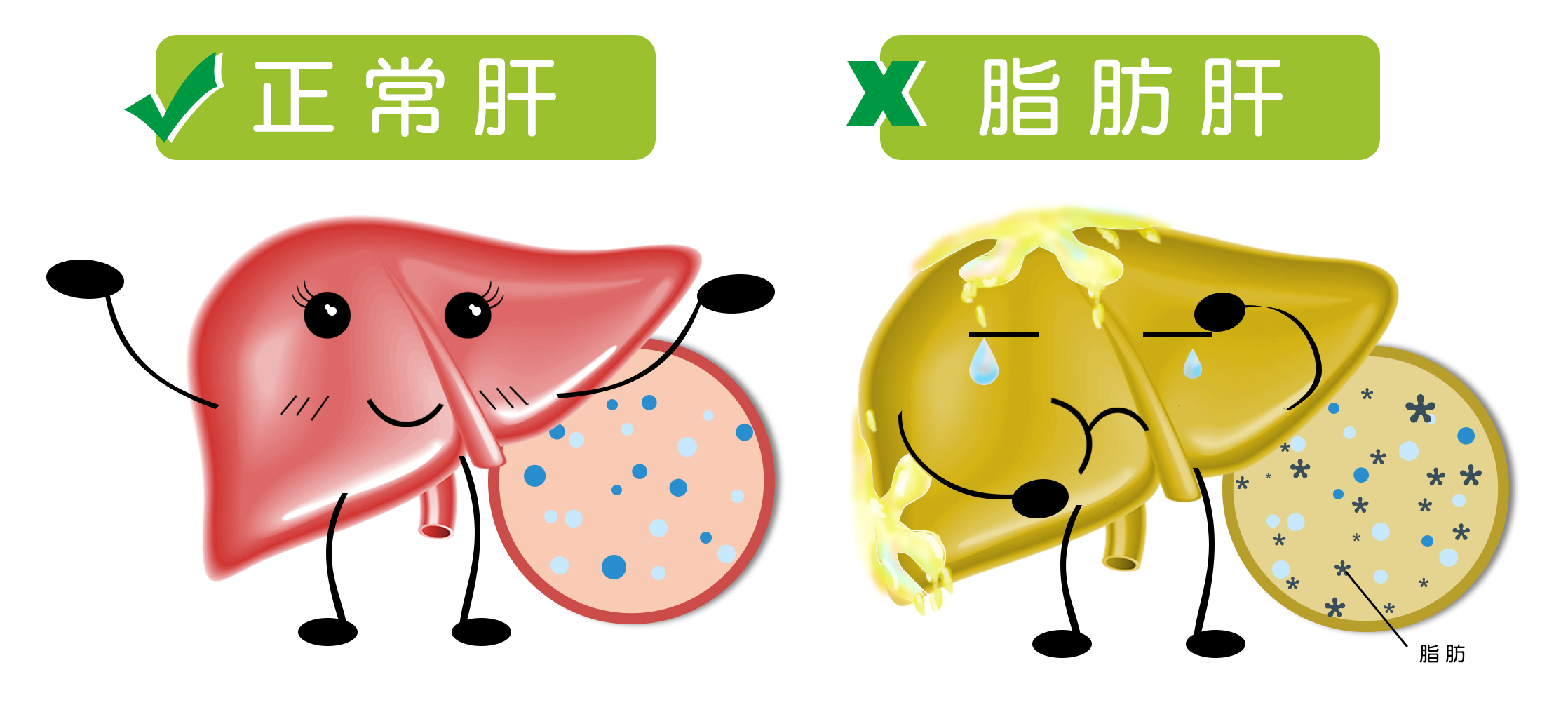

The core feature of fatty liver is the accumulation of lipid droplets in liver cells exceeding normal proportions (usually more than 5% of liver weight). Traditionally, people believe that "fatty liver" means "eating too much oil," but this is not the case. The main sources of fat in the liver include three pathways:

Reuptake of free fatty acids from adipose tissue (about 60%)

Fat intake from diet (about 15%)

Fat that the liver itself converts from carbohydrates (about 25%)

In other words, even if one does not eat much oil, if the daily diet is mainly composed of refined rice and flour, sugars, and high-calorie snacks, it is easy to form liver fat deposits due to "sugar turning into fat."

In addition, insulin resistance is a metabolic precursor to fatty liver. When the body's sensitivity to insulin decreases, glucose has difficulty entering cells smoothly and is forced to convert into fat stored in the liver. This is also why many fatty liver patients simultaneously have high blood sugar, high insulin levels, or even early-stage type 2 diabetes.

Therefore, dietary adjustments for fatty liver are not simply about "eating less oil" or "eating less meat," but rather require comprehensive interventions targeting blood sugar control, nutritional structure reconstruction, and metabolic pathways.

Core dietary goal: control energy density and insulin stimulation

The impact of dietary structure on fatty liver is far more profound than people imagine. First, two key terms need to be clarified: "energy density" and "insulin load."

Energy density refers to the calories contained in a unit weight of food. Foods with high energy density (such as fried foods, cream cakes, milk tea) not only have high calories but are also easy to overconsume unknowingly. In contrast, foods with low energy density (such as vegetables, whole grains, legumes) provide a sense of fullness while having relatively low calories.

Insulin load refers to the degree to which a certain type of food triggers insulin secretion after consumption. Foods with a high glycemic index (GI) and high insulin index can cause a rapid increase in insulin, stimulating fat synthesis and inhibiting fat breakdown, thereby increasing liver fat accumulation.

In practice, the diet should be adjusted towards "reducing energy density and controlling insulin stimulation," with the core including:

Choosing whole grains as staples (such as brown rice, oats, buckwheat), avoiding high GI carbohydrates like white rice and white flour

Avoiding sugary drinks, desserts, and fructose-concentrated beverages

Using vegetables and legumes to increase satiety, replacing high-calorie snacks

Having regular and measured meals, avoiding binge eating and late-night snacks

For example, a serving of 300 calories of potato chips (about 50 grams) may not be enough to make one feel full, while the same calories from brown rice with a serving of vegetable tofu soup can provide satisfaction and metabolic stability, which is the key to controlling energy density.

"Eating more vegetables" is not a panacea; pay attention to protein and fat structure

Many people, upon learning they have fatty liver, start eating vegetarian meals, "only eating vegetables, fruits, and porridge," trying to combat "greasiness" with "lightness." However, if such adjustments are unbalanced, they can backfire.

The repair of the liver and the process of fat metabolism rely on sufficient high-quality protein. Insufficient protein intake can lead to a decrease in the renewal rate of liver cells and even cause fatty liver to progress to liver fibrosis.

Recommended sources of protein:

Animal protein: such as skinless chicken, sea fish, eggs (be careful not to only eat egg whites and neglect the choline in the yolk)

Plant protein: such as tofu, soy milk, chickpeas, quinoa, etc.

Fats should not be completely denied either. Quality fats play a regulatory role in fat metabolism, especially foods rich in ω-3 fatty acids, which can improve inflammation related to fatty liver.

Preferred sources of fat include:

Flaxseed oil, olive oil, nuts (in moderation)

Salmon, mackerel, and other deep-sea fish (not fried)

Conversely, the following sources of fat should be avoided:

Refined vegetable oils (such as repeatedly heated restaurant oils)

Animal fats (lard, beef tallow)

Foods containing trans fats such as cream, shortening, and plant-based creamers

Therefore, a truly scientific diet is not merely about pursuing "lightness," but about controlling "bad fats," supplementing "good proteins" and "good fats," along with a reasonable carbohydrate structure to achieve a rebalancing of liver metabolism.

Is intermittent fasting and low-carb diet suitable for fatty liver?

In recent years, low-carbohydrate diets (Low Carb) and intermittent fasting (Intermittent Fasting) have been widely applied in dietary treatments for metabolic syndrome, obesity, and fatty liver. Studies have shown that these two methods can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce liver fat in specific populations.

Advantages of low-carb diets:

Rapid reduction of liver triglyceride levels

Lower fasting insulin levels

Improvement of liver enzyme indicators (such as ALT, AST)

Precautions:

Strict low-carb or ketogenic diets are not suitable for everyone, especially those with high uric acid or kidney disease should be cautious

Initial stages may experience "low-carb adaptation reactions," such as fatigue, dry mouth, and constipation, and adjustments should be made gradually

Advantages of intermittent fasting:

Reduction of total calorie intake

Enhanced fat oxidation

Promotion of cellular "autophagy," which may help liver repair

Common patterns include 16:8 (restricting eating to 8 hours a day) or 5:2 (controlling calorie intake for two days a week). However, for underweight individuals, those with stomach issues, or diabetic patients, it should be attempted under the guidance of a doctor or nutritionist.

The key to these strategies is "tailored." Regardless of the method, sustainability and nutritional balance are always the bottom line.

Food choices are more critical than total calories: low sugar ≠ high nutrition

One misconception in dietary intervention for fatty liver is "calorie fear." Many patients blindly choose so-called "low-cal" foods and sugar-free drinks, neglecting nutritional density and processing levels.

The following common dietary misconceptions are worth noting:

Replacing plain water with sugar-free drinks seems to control sugar but actually stimulates insulin secretion

Only eating fruits instead of regular meals leads to excessive fructose intake, putting more burden on the liver

Only consuming "light salads" but using high-fat, high-sodium dressings is counterproductive

Starvation dieting may seem to lead to weight loss in the short term, but long-term rebound is faster, causing deeper liver damage

Therefore, in dietary interventions, more attention should be paid to nutritional density and processing levels:

Choosing natural ingredients > highly processed foods

Focusing on protein and vitamin intake > solely controlling calories

Incorporating appropriate exercise to boost basal metabolism

For example, changing breakfast from "white bread + jam" to "boiled eggs + brown rice porridge + stir-fried greens" may have slightly higher calories, but the nutritional quality and satiety significantly improve, which is more beneficial for liver function repair.

Case analysis: the transition from "eating less" to "eating right"

Case 1: Mr. Lin, 35 years old, IT engineer

During a health check-up, he was found to have moderate fatty liver. He started eating very little, relying only on plain porridge and vegetables for his diet. Although his weight dropped by 5 kilograms, his serum transaminases rose after a month, and he felt fatigued, even developing mild hypoproteinemia.

Under the guidance of a nutritionist, he adjusted to regular meals with protein, healthy fats, and low GI staples: adding eggs and mixed grain porridge for breakfast, using tofu instead of red meat for lunch, and choosing steamed fish with leafy greens for dinner. After three months, his liver enzymes decreased, body fat reduced, and his mental state significantly improved.

Case 2: Ms. Wang, 42 years old, normal weight but has fatty liver

She is not overweight, enjoys drinking juice, eating desserts, and sitting for long periods, and initially did not realize the risk. After being diagnosed with fatty liver, she began to pay attention to "sugar load," switching from juice to tea, only consuming desserts occasionally during holidays, and taking a 30-minute walk after dinner. After six months, her liver ultrasound returned to normal, and her blood sugar fluctuations stabilized.

These two cases illustrate that dietary adjustments for fatty liver cannot only focus on calories but must also consider metabolic logic, nutritional structure, and behavioral habits.