Great Viet once made Southeast Asian countries bow in respect. That was during the 15th century, the golden age of the Le dynasty, under the reign of King Le Thanh Tong, one of the greatest kings in Vietnamese history. At this time, Great Viet was not just a small nation but was a true power. The economy developed with prosperous agriculture and bustling trade. The army was organized tightly with hundreds of thousands of elite soldiers trained systematically, equipped with war elephants and war horses. The political system was stable, the laws were clear, and the officials were honest.

King Le Thanh Tong, the man behind it all, was not only an excellent military leader but also a brilliant reformer. He enacted strict laws, reorganized the army, and expanded education. However, Southeast Asia in the 15th century was not a peaceful land. Kingdoms like Lan Sang, now Laos, Ayutaya, now Thailand, Champa, and Chenla, now Cambodia, were strong forces continuously vying for influence. Particularly, the relationship between Great Viet and Lan Sang had been tense since the early 14th century when Lan Sang frequently disturbed the northwestern border.

By the 15th century, specifically in 1478, a general from Lan Sang captured a white elephant, which was considered a sacred treasure in Southeast Asia at that time. The white elephant was not only a symbol of strength but also of authority and was seen as an omen of good fortune, bringing great prestige to any king who possessed it. From Lan Sang, Siam to Myanmar, everyone yearned for a white elephant. When news of the white elephant reached Great Viet, King Le Thanh Tong sent an envoy to Lan Sang to request a gift of some elephant hair, a common diplomatic gesture that expressed friendliness and demonstrated a good relationship.

However, the crown prince of Lan Sang, who had never liked Great Viet, shocked everyone by sending not the requested elephant hair but instead sent elephant dung and a beautifully carved chest as a gift. Imagine this scene: in the Great Viet court, the envoy opened the chest in front of King Le Thanh Tong and the high-ranking officials. A foul smell arose, and the entire court fell silent. This was not only an insult but also a slap aimed directly at the prestige of Great Viet. King Le Thanh Tong, known for his calm demeanor, was truly furious this time. He swore to make Lan Sang pay the price.

At the same time, in the northwest region, Bồn Man, now part of Laos, a vassal of Great Viet, suddenly turned against them. The chieftain, wielding a spear, allied with Lan Sang to raid the Quy Hop region, now Nghệ An. This was the last straw, prompting King Le Thanh Tong to decide to mobilize troops. In July 1478, King Le Thanh Tong ordered the mobilization of a massive army, about 180,000 elite soldiers, divided into five groups led by top generals. A sea of people, thousands of war elephants, war horses, battle flags filling the sky, and the sound of drums echoed. This strategy created a pincer movement that tightened around Bồn Man and Lan Sang from all directions.

The Great Viet army was not only numerous but also well-trained, coordinated, and led by talented generals. On the opposite side, Lan Sang did not stand idly by. According to Lao history, they mobilized about 200,000 troops, 2,000 war elephants, and six talented generals under the command of the Lao crown prince. They were even supported by the Lan Sang kingdom in northern Thailand. But would their large numbers and war elephants be enough to stop the war machine of Great Viet?

The Great Viet army launched their campaigns like a storm, quickly crossing Bồn Man and crushing all resistance. The Lan Sang troops fell like ripe fruit, especially the crown prince of Lan Sang, the one who sent the elephant dung, who was severely injured and ultimately captured. Seeing the dire situation, the king of Lan Sang hurriedly fled the capital Luong Pha Bang, escaping to Chieng Khan in the Lan kingdom. The Great Viet army advanced straight into the capital with little resistance, seizing countless gold, silver, food, and weapons.

But they did not stop there; the Great Viet army, with their overwhelming strength, continued to pursue the entire Lan Sang army to the Ibraadi River basin in present-day Myanmar. They even attacked Lan Sang and Utaya, now Thailand, causing these two kingdoms to tremble before the might of Great Viet. After defeating Lan Sang, Great Viet returned to deal with Bồn Man. In 1479, although the leader of Bồn Man resisted fiercely, King Le Thanh Tong sent Le Niem to lead a massive army, reportedly 300,000 troops, to attack. The Great Viet army overcame treacherous passes, crushed the resisting forces, and eliminated the leadership.

To stabilize the newly acquired land, King Le Thanh Tong implemented a very clever strategy. He appointed Cam Dong, the brother of the former king, as the ambassador to help win the hearts of the Bồn Man people, and Bồn Man was officially annexed into Great Viet. After these battles, King Le Thanh Tong annexed Bồn Man, helping to expand the territory of Great Viet. Southeast Asian countries like Champa, Chenla, Lan Sang, Chiang Mai, and Ayutaya, as well as Java in present-day Indonesia, had to submit according to Volume 3 of Vietnamese history from the Institute of History.

So how exactly did this happen?

Regarding Champa, Champa was a kingdom located in central Vietnam and one of the important neighboring countries of Great Viet. During the reign of Le Thanh Tong, Champa had significantly declined compared to its peak. When King Le Thanh Tong organized large military campaigns against Champa to retaliate for sporadic attacks and assert the authority of Great Viet, Champa was subdued, directly attacking the capital of the opponent, annexing most of Champa's territory into Great Viet.

After the defeat, Champa became a vassal, forced to pay tribute periodically to the Thang Long court. This vassal relationship was not only symbolic but also helped Great Viet control coastal trade routes and access characteristic products of Champa such as agarwood and ivory. The submission of Champa reinforced the position of Great Viet as a regional power while minimizing threats from the south.

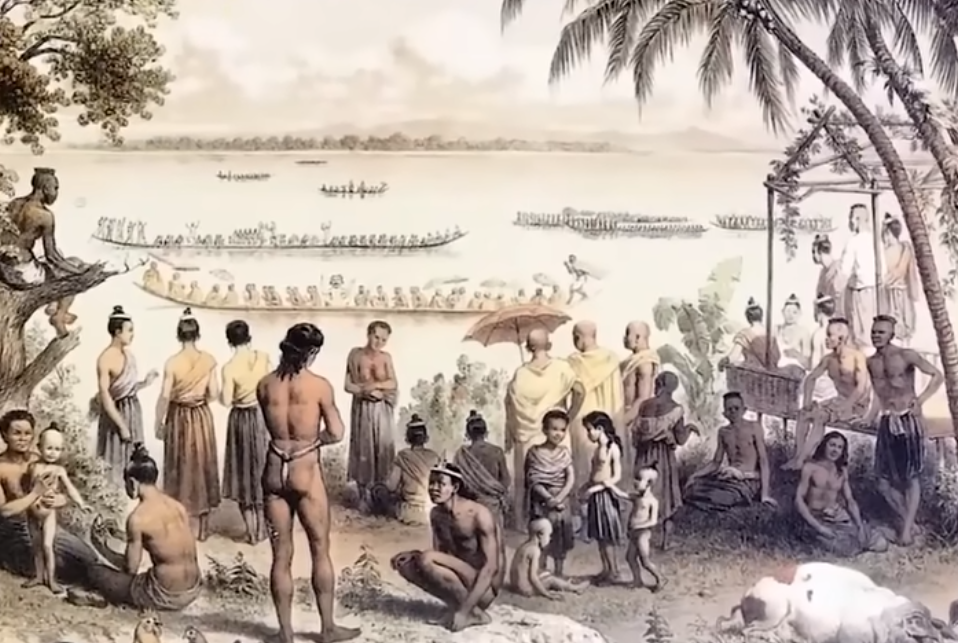

As for Chenla, now Cambodia, this was a kingdom located in the Mekong River basin, famous for its brilliant Angkor civilization inherited from the past. However, in the 15th century, Chenla weakened due to civil wars and pressure from neighboring forces. Under King Le Thanh Tong, Great Viet did not conduct direct military campaigns against Chenla, but the military strength and prestige of Great Viet forced Chenla to accept a vassal status.

According to Volume 3 of Vietnamese history, Chenla paid annual tribute to Great Viet, demonstrating recognition of the authority of the Thang Long court. This relationship brought economic benefits to both sides. Great Viet could access products such as rice, dried fish, and precious wood from the Mekong basin while Chenla received political patronage to maintain stability against rivals like Ayutaya. The vassal relationship with Chenla reflected the diplomatic flexibility of King Le Thanh Tong in expanding influence without military conflict.

Chiang Mai, now in northern Thailand, part of the Lan Na kingdom, was an important cultural and trade center in the region, and in the 15th century, Lan Na maintained a complex relationship with neighboring countries like Ayutaya and Great Viet. Although there is no evidence of a direct military campaign by Great Viet against Chiang Mai, Vietnamese history records that Chiang Mai became a vassal of Great Viet under King Le Thanh Tong, possibly due to pressure from Great Viet's military victories in the region, especially the campaign against Lan Sang.

Regarding Ayutaya, Ayutaya is now Thailand, one of the most powerful kingdoms in Southeast Asia in the 15th century with a prosperous economy, trade, maritime, and agriculture. Although Ayutaya was a competitor to Great Viet, Vietnamese history records that under King Le Thanh Tong, Ayutaya became a vassal and paid tribute to Great Viet. This may have stemmed from diplomatic negotiations or indirect pressure from the military strength of Great Viet, especially after victories against Lan Sang and Champa.

Ayutaya's acceptance of vassal status, although symbolic, indicates the flexibility in the diplomatic policy of this kingdom to maintain peace and trade with Great Viet. This relationship helped Great Viet access products such as spices, fabrics, and handicrafts, while also reinforcing Great Viet's position in the region. However, this relationship may not last long as Ayutaya also maintained a vassal relationship with the Ming dynasty in China.

As for Java, now part of Indonesia, the 15th century was the center of maritime kingdoms, a powerful empire in trade and culture. Java is recorded as one of the countries that paid tribute to Great Viet under King Le Thanh Tong. Due to the distant geographical location, Java's status as a vassal may not have stemmed from direct military pressure but from trade and diplomatic relations.

Thus, the vassal system under King Le Thanh Tong included countries such as Champa, Chenla, Lan Sang, Chiang Mai, Ayutaya, and Java. This is evidence of the military, diplomatic, and economic strength of Great Viet. These relationships were not only symbolic but also promoted trade, helping Great Viet access diverse resources and products from across Southeast Asia.