The Grand Aspirations and Real Limitations of Idealism

Zhuge Liang's "Six Expeditions to Qishan" began with a profound concern for the fate of the country. After Liu Bei's death, the Shu Han regime was weak, facing the strong enemy Cao Wei to the north and the unreliable ally Eastern Wu to the east. The only way to break the deadlock was to take the initiative to attack and shift from defense to offense. This was precisely the strategic thinking expressed by Zhuge Liang in the "Memorial on the Expedition": "Be close to virtuous ministers and distant from petty people; this is how the Former Han thrived; be close to petty people and distant from virtuous ministers; this is how the Later Han declined."

However, while the ideals were grand, the reality was harsh. The national strength of Shu Han was already insufficient, with a limited population, tight military resources, and a lack of supplies, making it like striking a stone with an egg compared to Wei. After Liu Bei's defeat at Baidi, morale in Shu did not recover; although the southern regions had been pacified, the people's hearts were not solidified. The terrain around Qishan was steep and difficult for supplies, and each northern expedition almost challenged the limits of logistics.

In this context, Zhuge Liang believed that "attack was unavoidable," but "attacking was difficult to achieve." The ideal strategic vision was constantly interrupted by reality, making the six expeditions to Qishan neither a victorious breakthrough nor a sustainable war of attrition. Each expedition was a gamble that consumed national strength, with outcomes yielding only temporary victories or dismal retreats.

Was the Qishan Strategy Doomed to Be Futile?

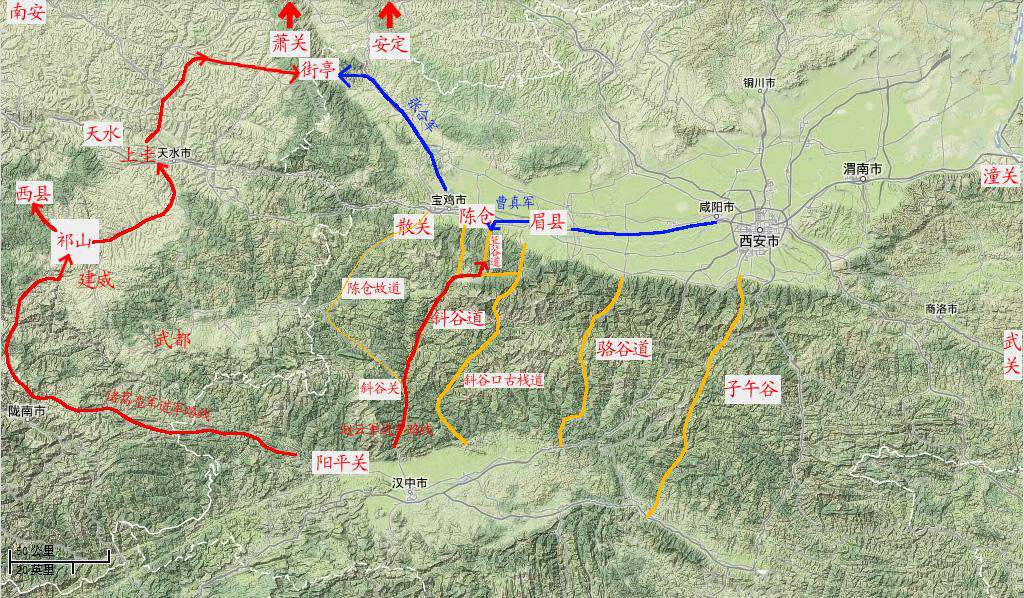

From a geographical and military perspective, Qishan was indeed a weak point in Wei's defense line. Compared to the key areas of Guanzhong and the important stronghold of Chang'an, Qishan's defenses were weak and troops were scattered, making it an important entry point into Cao Wei. However, the problem was that even if Zhuge Liang broke through Qishan, it would be difficult to advance further. Between Hanzhong and Guanzhong lay complex mountains and winding roads; deep into enemy territory, the army resembled a long snake probing its head, easily cut off from supplies.

More importantly, Shu Han lacked follow-up support and strategic depth. With Wei's strong national power, even if they temporarily lost territory, they could quickly redeploy troops and reorganize; whereas for Shu Han, losing even a single general or soldier would be a significant blow. For example, during the first northern expedition, Ma Su lost the strategic point of Jieting, not only losing territory but also severely damaging morale and Zhuge Liang's personal reputation. Even if Zhuge Liang personally donned armor and supervised the battle, it was difficult to resolve the personnel obstacles of "unity of purpose."

A deeper question is: could the northern expeditions really "secure Shu Han by reclaiming the Central Plains"? In other words, was Qishan truly the pathway to "restoring the Han dynasty," or was it the only frontline Zhuge Liang had to choose in his ideals? History seems to provide an answer leaning towards the latter. Even if Qishan were occupied, there would still be the entire Chang'an defense line to face, with Wei's strongholds heavily garrisoned, advancing step by step; how could a lone army shake this?

Therefore, from a military perspective, while the "Six Expeditions to Qishan" had tactical ingenuity, it was always difficult to establish a strategic depth that determined victory or defeat. Each expedition was akin to an "impulse supported by reason."

The Political Metaphor of "Heaven's Mandate is Hard to Defy"

In "Romance of the Three Kingdoms," Zhuge Liang lamented before his death that "Heaven's mandate is hard to defy," as if it had already been predetermined that his northern expeditions would not end well. Although this is a literary embellishment, it reflects the profound influence of the concept of "Heaven's mandate" in political narratives at the time. In an era of frequent dynastic changes and power vacuums like the Three Kingdoms, who was the "mandate of heaven" was a legitimacy question all rulers needed to answer.

The Shu Han regime represented by Zhuge Liang, from its founding, claimed to be the "orthodox of the Han dynasty," emphasizing "the mandate is with Liu" and the historical mission of "restoring the Han dynasty and reclaiming the Central Plains." This narrative of values supported the legitimacy of Shu Han and shaped Zhuge Liang's political persona of "dedication and selflessness."

However, once the "mandate" could not be fulfilled, it could transform into a heavy shackle of "fate." After repeated defeats, the people's faith gradually eroded, the will of the generals began to waver, and even Zhuge Liang himself increasingly doubted whether the "mandate" truly resided in Shu. The six expeditions yielded no results, and he ultimately died in the army, becoming a symbol of "exhausted plans and efforts," while "Heaven's mandate is hard to defy" became a historical footnote to all his efforts—both a comfort and a way to shirk responsibility.

This narrative logic reflects the ancient people's cultural response to historical failures: if not due to lack of talent, then it must be due to fate. This is both a form of tragic aesthetics and a psychological compensation mechanism for the legitimacy of power.

Organizational Structure and the Limitations of the Shu Han System

Whether ideal military concepts can be realized depends on whether the system can support them. Although Shu Han nominally established a system of three provinces and six ministries, its organizational structure and human resources were far inferior to those of Wei. Zhuge Liang held multiple positions, being both the chancellor and leading troops into battle, with political and military affairs almost inseparable, which not only led to excessive centralization of power but also caused political stagnation during the northern expeditions.

More critically, Shu Han lacked a stable and reliable team of mid-level generals. Ma Su was all talk and no action, Wei Yan was unruly and difficult to tame, Li Yan was duplicitous, and although Fei Yi and Jiang Wei had talent, they only began to show their abilities after Zhuge Liang's death. This situation of "the chancellor single-handedly supporting the overall situation" made the six expeditions a series of implementations of "personal will" rather than institutionalized strategy.

In contrast, Wei had a mature military command system, an institutionalized supply system, and a relatively complete political structure. Even after Cao Cao's death, his regime continued, with figures like Sima Yi, Cao Zhen, and Guo Huai capable of acting independently. Shu Han, however, relied entirely on Zhuge Liang's talent; losing him was like losing a backbone.

Therefore, the defeat of the "Six Expeditions to Qishan" was not just a matter of strategic choice but also a result of the system's failure to support strategic actions. No matter how high the plans were, without the means to execute them, even Zhuge Liang's utmost efforts could not resolve the dilemma of "a clever woman cannot cook without rice."

The Wise Man Who Died at Wuzhangyuan and the Embodiment of Cultural Ideals

Zhuge Liang died at Wuzhangyuan, famously said to have "fallen like a star," and his image reached the pinnacle of idealism in "Romance of the Three Kingdoms." He represented not just a strategist but the total spirit of the "scholar": loyalty, intelligence, integrity, endurance, and a heart for the world.

Later generations' evaluations of him often transcend success and failure. For example, Lu You's "Book of Resentment" states: "The memorial for the expedition truly names the world; who can stand between the ages?" Du Fu also remarked, "The expedition was not yet successful, but he died first, causing heroes' tears to fill their sleeves." This emotional projection is not only due to Zhuge Liang's exceptional intelligence but also because he embodied the conflict and fusion of "loyalty and fate" throughout his life.

In the Confucian discourse system, failure is not a denial but a fulfillment. Although the six expeditions to Qishan did not achieve victory, they validated the moral logic of "doing one's best and leaving the rest to fate." After Zhuge Liang's death, his personal brilliance even surpassed his political achievements during his lifetime, becoming a model of loyalty and a symbol of wisdom. This reflects the traditional Chinese cultural way of "moralizing history"—the value of historical events lies not only in the results but also in the moral stance they represent.

Therefore, "Heaven's mandate is hard to defy" is not merely a cause of failure but also an expression of the historical tragedy of "ideals cannot triumph over reality," as well as a gentle empathy from cultural psychology towards loyal but failed individuals.

Jiang Wei's Continued Failures and the Twilight of Idealism

After Zhuge Liang's death, Jiang Wei inherited his will and continued the northern expeditions, attacking Wei more than ten times and even proposing the idea of "uniting with Eastern Wu to attack the Central Plains." However, the results were still dismal, with national strength further weakened and the people exhausted, ultimately leading to the rapid demise of Shu Han after Deng Ai's stealthy crossing of Yinping.

Although Jiang Wei's military talent was high, it was far inferior to Zhuge Liang's overall planning ability. His continuous northern expeditions failed to shake Wei but completely drained Shu Han's national strength reserves. It can be said that Jiang Wei did not understand the strategic focus of Zhuge Liang's "northern expeditions"—during Zhuge Liang's lifetime, the northern expeditions were both offensive and defensive, attempting to shift the enemy's focus through proactive strikes and stabilize his own regime; whereas Jiang Wei turned it into a purely military adventure, ultimately leading idealism to the end of the nation.

The fall of Shu Han became the epilogue of the "Six Expeditions to Qishan." This history tells us: if ideals cannot be integrated into systems and reality, they will only become an aesthetic legacy of history, available for future generations to reminisce about, but difficult to serve as the foundation for nation-building.