In an inconspicuous five-story building on the outskirts of Guangzhou, a special experiment on the dignity of life and social responsibility is underway. The first to third floors of this building are private dialysis centers, while the fourth floor is a busy clothing factory, where 58 uremia patients play the dual roles of patients and workers. The oldest of them is 60 years old and the youngest is only 18 years old. They shuttle between the dialysis machine and the sewing machine every day, pay for the dialysis fee with the income from sewing clothes, and then continue to work with their bodies after dialysis. This "uses industry-procurement medicine" model not only demonstrates the survival wisdom of uremia patients to improve themselves, but also reflects the systemic dilemma faced by my country's chronic kidney disease group. This article will deeply analyze the causes, operating mechanism, positive significance and potential problems of this phenomenon, and explore how to build a more complete social security system for uremia patients.

Uremia, as the end-stage manifestation of chronic kidney disease, has become a challenge that cannot be ignored in the field of public health in my country. According to statistics from the Chinese Kidney Disease Data System, as of the end of 2024, there were more than 2 million uremia patients in my country, of which 1.183 million were received for dialysis, and about 20,000 new cases were added every year. Behind these numbers are life stories that have been changed by diseases. People with uremia need to rely on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for life to maintain their lives, usually three dialysis times a week, four hours each, and this treatment process will accompany them until the end of their lives.

The financial burden is the primary challenge facing patients with uremia. Although hemodialysis was included in the medical insurance for serious illnesses in 2012, and the reimbursement ratio in most areas increased to about 90%, the superposition of dialysis self-paid parts, complication treatment, drug costs, transportation and renting houses near dialysis centers is still a heavy burden on patients who have lost their ability to work. The differences in medical insurance policies in different regions have further aggravated this inequality - dialysis fees in some areas are only reimbursed by about 70%, and patients will have to pay 30,000 to 40,000 yuan per year; while some areas set up a reimbursement limit (such as 4,000 yuan per month), and the patient will bear the full amount of the excess. A worker from Hunan revealed that due to insufficient reimbursement amount in his hometown, he had to change the dialysis three times a week to 5 times a week, and he still had to pay more than 2,000 yuan per month, which was almost equivalent to the full monthly income of local rural families.

Employment discrimination poses the second obstacle. Uremia patients are often excluded by the labor market due to their physical strength decline and the need for regular dialysis. Before he got sick, Zhang Shun was a skilled tailor in a coastal garment factory. He spent decades of work to get a house in the county. After he got sick, he went to seek medical treatment, and his savings, work, marriage, and his remaining urination ability were lost, and he was eventually trapped in his hometown and "sitting for nothing." Similar encounters are extremely common among uremia groups - they have worked in various occupations such as deliverymen, drivers, and decoration workers, but after getting sick, they were fired and treated as a "burden". Many people try to hide their illness "like a thief" work, or choose night shifts to cooperate with daytime dialysis, but eventually they return to the hospital bed because they are overwhelmed.

Social isolation is the third invisible blow. The life in my hometown described by a uremia patient is full of loneliness and stagnation: "The days are growing on two beds, one at home, the windows are closed; the other is in the hospital, 'The black and mom patients are nailed in the increasingly crowded dialysis room'." Connecting these two beds is an electric car that "life-strips" three times a week without any resistance. In areas with scarce medical resources, some patients even need to travel long distances to municipal hospitals for dialysis. Data from the National Health Commission in 2025 shows that there are still 72 counties in the country with a permanent population of more than 100,000, and their public comprehensive hospitals do not have hemodialysis service capabilities.

It is this systemic dilemma that gave birth to Guangzhou's "use engineering to support medical care" model. Starting from 2021, the changes in two policies have created conditions for uremia patients to make a living in other places: First, the National Health Insurance Administration has launched a pilot program of cross-provincial direct settlement of outpatient chronic disease treatment costs, and included uremia dialysis; Second, Guangdong Province is the first to cancel the restrictions on insured household registration for flexible employment personnel. Taking advantage of this, dozens of private dialysis centers in Guangzhou have begun to try the "medical-employment" combination model, attracting uremia patients from all over the country. These centers usually have dialysis rooms on the second and third floors, and garment factories, handicraft workshops on the fourth floor. Patients work here to earn money to pay medical expenses, forming a self-sufficiency micro-ecosystem.

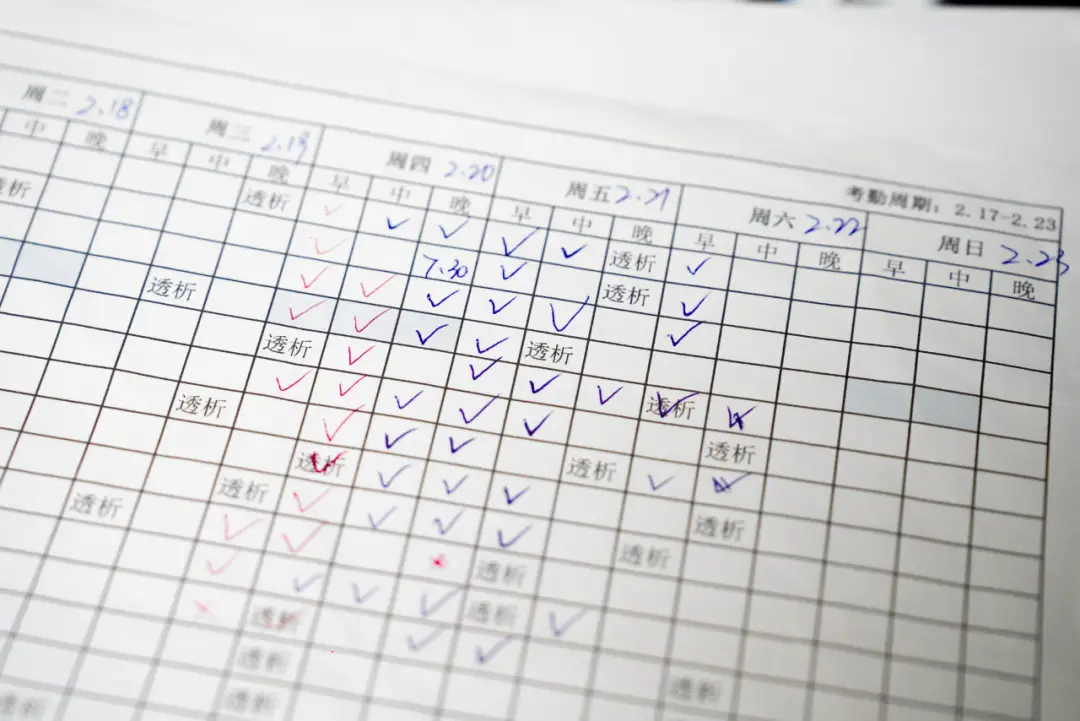

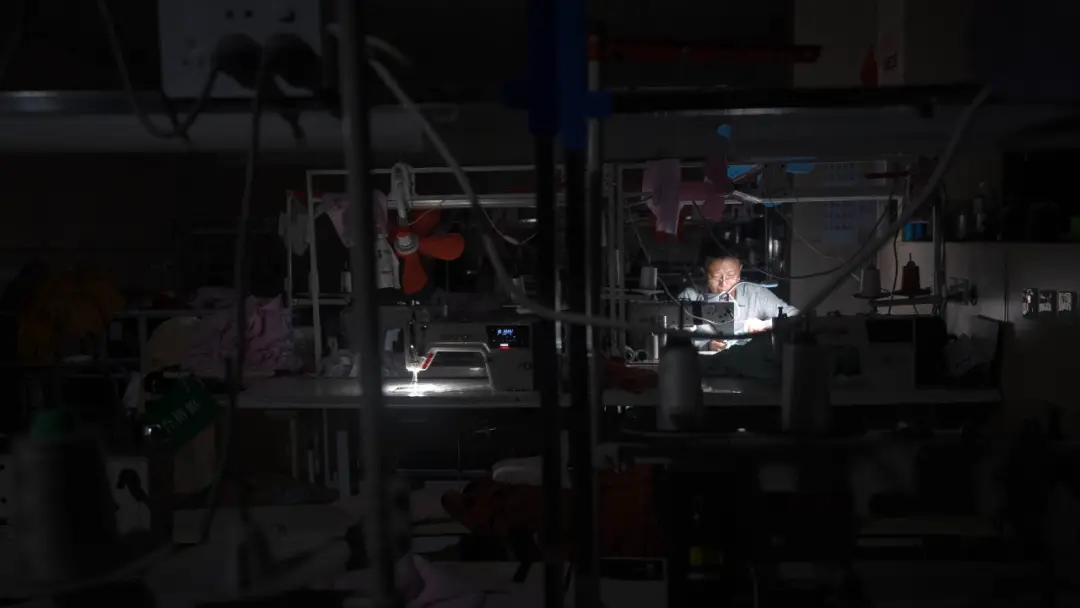

The five-story building of this private dialysis center in the suburbs of Guangzhou is actually a carefully designed "medical-industrial complex". Early in the morning, a group of workers with dialysis blood vessels raised on their arms flooded into the building, starting a day-to-day survival cycle. In the fourth floor garment factory, 58 pairs of black and thin hands shuttled between sewing machines, good-skilled car pants, careful thread cutting heads, good-eyed checking goods, and older cleaning waste cloth strips - different processes are allocated according to their respective physical conditions, and the daily production capacity can reach up to 2,000 pieces. At noon, workers took the elevator in batches to the dialysis room on the third floor, transforming from producers to patients, allowing machines to replace the failed kidneys to filter the toxins in the blood. Four hours later, they returned to the production line until after ten o'clock in the evening.

The economic logic of this model is reflected in two levels. For patients, income and dignity are obtained through labor, while ensuring that treatment is not interrupted. "You can't save money, but you can support yourself." When the factory supplies food and accommodation and provides a monthly "water control bonus of 400 yuan", the workers' wages can basically cover medical and living expenses. As a "model worker", Zhang Shun earns about 4,500 yuan per month. After deducting all expenses, more than 1,000 yuan of surplus will be used to get nutritional injections (238 yuan/injection), and "you have the strength to continue making money after the injection." For dialysis centers, this model not only ensures a stable source of the disease (nearly half of the beds in such centers in Guangzhou are occupied by "working patients"), but also obtains sustainable medical income through medical insurance reimbursement.

Psychological and social benefits are also significant. Zhang Shun remembered the supervisor's words "The wind cannot blow, the rain cannot blow, so that we patients can live a normal life" very deeply. For patients with uremia who have been exposed to social exclusion for a long time, being able to support themselves and no longer become a burden on the family, the value of this sense of dignity is difficult to measure with money. After losing her job due to illness, Qiu Xiulan "lived" at her home in Yunnan for five years, relying on her husband to support and take care of her two children. After coming to Guangzhou, she regained her economic autonomy and social identity. The mutual aid culture among workers also alleviates loneliness - there is not enough time to share, "giving some work to have children at home" has become an self-evident rule.

However, this model is also in the gray area of rules, causing a lot of controversy. First of all, there are safety risks in the mixing of medical places and production workshops. There are scenes where protein powder is mixed in the water cup and quick-acting heart-saving pills and rainbow candy are prepared during dialysis, which implies health risks. Secondly, uremia patients should have ensured sufficient rest, but Zhang Shun and others' work intensity "7 a.m. to 10 p.m." obviously exceeds medical advice. Furthermore, this model essentially relies on medical insurance funds - Guangdong's dialysis fee reimbursement ratio is about 90%, and the "benefits" created by patients' labor actually come from public medical funds. Finally, legal issues such as work-related injury identification and labor rights protection are still in a vacuum.

The deeper ethical dilemma is: is this real empowerment, or is it another form of exploitation? Private dialysis centers do provide patients with space for survival, but patients have also become the key resource for the center to achieve "medical revenue". Is this interdependence balanced? When "model worker" Zhang Shun needs to pay for the nutritional needle through overload work (one needle is equivalent to the wage of sewing 600 pairs of trouser legs), what we see is a sad "survival inclination". The hierarchical differentiation on the production line - healthy workers dominate the "head workshop", and kidney-friend workers accumulate at the "tail" with low technical threshold, further reflects the limitations of this model.

From a broader perspective, the dilemma of the uremia group reflects the shortcomings of my country's chronic disease management system. The development cycle of chronic kidney disease can last up to 20 years, but early screening and intervention mechanisms are missing, and many patients are not diagnosed until the end of the period. The early expenditure of "dead horses are treated as live horses" has emptied their assets. Although the inclusion of dialysis into the medical insurance for major illnesses has alleviated economic pressure, the full-cycle management of prevention, treatment and rehabilitation has not yet been formed. When 2 million uremia patients generate 150 billion yuan in theoretical treatment needs every year, relying solely on post-event medical assistance is obviously unsustainable.

Guangzhou's "uses industry to support medicine" model is the grassroots innovation that has grown in these institutional gaps. It not only takes advantage of the opportunity window for loosening medical insurance policies, but also responds to the need for private dialysis centers to obtain stable disease sources, and also meets patients' desire for work dignity. However, the sustainability and replicability of this model are still questionable - it relies heavily on specific policy environments (such as Guangdong's higher dialysis reimbursement ratio), regional economic characteristics (such as Guangzhou's clothing industry chain), and patient group characteristics (such as middle-aged and young patients with labor skills).