This is a period when Japan was almost completely closed off from the outside world, living for over 200 years under a policy known as Sakoku or National Isolation. So why did Japan choose such a secluded path? What was life like for the people during that time? Were they really completely isolated? And what made Japan both unique, traditional, and mysterious during this period? That was the Edo period.

Before the Edo period began, Japan was immersed in a time known as Sengoku, a prolonged civil war lasting over a century, where feudal lords constantly fought for power. By 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu, a brilliant strategist, unified Japan and became the Shogun, the most powerful general at the head of the Tokugawa shogunate. But unifying the country was just the first step. He and his successors faced a major challenge of how to maintain power and ensure long-term security. Their answer was Sakoku, the policy of closing the country.

But why did they choose this path?

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Western countries such as Portugal, Spain, and the Netherlands began to set foot in Japan. They brought goods, weapons, especially firearms, and even Christianity. Initially, Christianity was welcomed by some feudal lords and the populace, especially in southern Japan. However, the Shogunate saw the danger of Christianity not just as a religion but also as a tool for Western countries to expand their political influence. If the people converted en masse, their loyalty to the Shogunate could be undermined. Moreover, missionaries often accompanied merchants and armies, a scenario the Shogunate did not want to repeat.

In 1635, the Shogunate issued a ban on Christianity and expelled most foreigners. Those who did not comply faced severe consequences. Christian believers were persecuted, most famously in the Shimabara Rebellion, where tens of thousands of Christians were massacred. Subsequently, the Sakoku policy was tightened more than ever. Along with that, the Shogunate wanted to build a stable society where everything was tightly controlled. They were concerned that free trade with foreign countries would enrich and empower local feudal lords, who could challenge central authority. Especially, firearms from the West were revolutionary.

If feudal lords possessed too many modern weapons, the risk of civil war would return. Closing the country helped the Shogunate control the flow of weapons, goods, and information. The 17th century was a time when Western countries expanded their colonies throughout Asia. The Philippines was occupied by Spain. Southeast Asia fell into the hands of the Dutch and the British, and the Shogunate saw the danger. If they opened up without control, Japan could become prey to empires. Closing the country was a way to protect themselves, at least until they were strong enough to cope. But closing the country did not mean complete isolation.

Japan still maintained some small trade channels mainly through the port of Nagasaki, where only the Dutch and Chinese were allowed to trade. This leads us to the next question. What was life like for the people during the Edo period after the country was almost disconnected from the world? Imagine you are a Japanese person in the 17th or 18th century. Your country is almost cut off from the outside world. Is life boring? The answer is absolutely not.

The Edo period is one of the most interesting phases in Japanese history, with a tightly organized society, a highly developed culture, and colorful everyday stories. This was a time when Japan was organized according to a system called Shinokosho, which is a very rigid social hierarchy resembling a giant pyramid. At the top were the samurai, who made up about 5 to 7% of the population. Samurai were not only brave warriors with swords in hand but also took on roles as officials, teachers, or even poets during peacetime. They were allowed to carry two swords, symbols of their status, but their lives were not always glamorous.

Many poor samurai relied on stipends from their lords and sometimes had to take on side jobs like paper-making. Next were the farmers. Farmers made up the majority of the population, about 80%. They were the backbone of society as they produced rice, the most important resource. However, farmers faced heavy taxes, sometimes up to 40-50% of their harvest. They were bound to the land, not free to move, and their lives often revolved around the agricultural cycle. Below the farmers were the artisans. They produced handcrafted items such as ceramics, textiles, wooden goods, or metalwork.

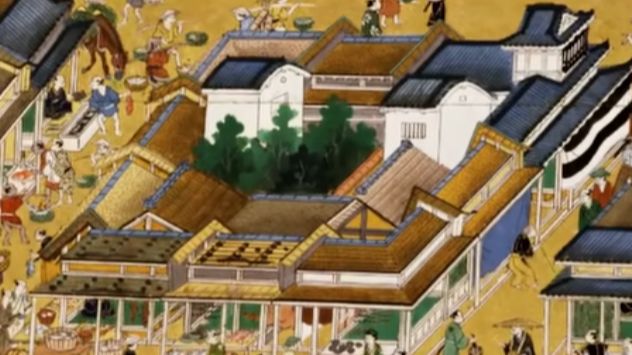

Artisans in large cities like Kyoto were famous for their exquisite techniques, from paper fans to elaborate kimonos. And finally, there were the merchants. Although ranked the lowest in the hierarchy, they were the wealthiest. Merchants in large cities like Edo and Osaka accumulated vast fortunes from trade, lending, and business. Many samurai even had to borrow money from them, leading to an underground upheaval in society. In addition to the four main classes, there were groups considered marginalized, such as the Eta, who did unclean jobs like leatherworking, and Hinin, who were homeless, criminals, or vagabonds. These people were ostracized by society, living in separate areas, but they also contributed to the diversity of the Edo period, where the shogunate controlled society with a strict system of rules.

For example, each class had to wear specific clothing, not exceeding limits. A farmer daring to wear silk kimono like a merchant? They could be heavily fined. This system ensured order but also created dissatisfaction, especially among the lower classes. Most Japanese people during the Edo period lived in rural areas in small villages surrounded by rice fields and mountains. Their lives revolved around agriculture, mainly rice and soybean cultivation. A farmer's day began early in the morning when they went to the fields to work and ended when the sun set. Houses were often simple wooden structures with thatched roofs and a hearth in the middle for warmth and cooking. Despite the peaceful rural life, farmers faced great pressure from taxes.

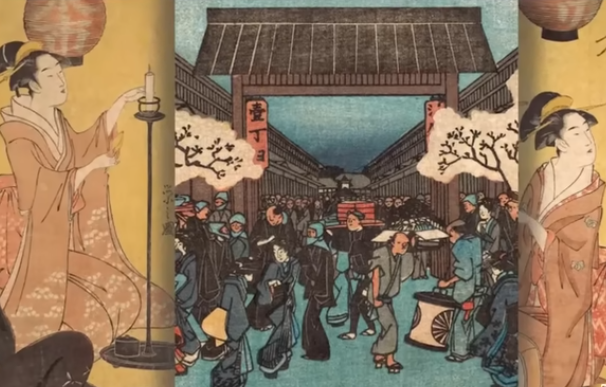

The shogunate and feudal lords collected taxes in rice, leaving families with just enough to survive day by day. Occasionally, when harvests failed or taxes were too heavy, farmers would revolt, but these uprisings were usually suppressed quickly. If the countryside was a tranquil place, then large cities like Edo, present-day Tokyo, or Osaka and Kyoto were bustling centers. Edo in the 18th century was one of the most populous cities in the world, with over 1 million people.

People during this time knew how to enjoy life despite being bound by many rules; entertainment was an essential part, from grand festivals to simple pleasures. Religion also played an important role in Edo life. Shinto and Buddhism were the two main religions often intertwined in daily life. Each village had a Shinto shrine for prayers for peace, and Buddhist temples were places for funerals or memorial services. The Shogunate encouraged everyone to register at a temple to control the population and prevent Christianity.

Even in a closed society, Japan during the Edo period placed great emphasis on education.

Samurai studied Chinese characters, Confucianism, and martial arts. The literacy rate in Japan during the Edo period was very high compared to other countries, especially in urban areas. Despite being closed, Japan still absorbed knowledge from the West through Rangaku, or Dutch studies. At the port of Nagasaki, Japanese scholars studied Dutch books on medicine, astronomy, maps, and engineering. For example, they learned how to make barometers, studied human anatomy, and applied some military techniques. This helped Japan not to fall behind, although it was slower than the West. But life during the Edo period was not always rosy.

In addition to heavy taxes, people also faced natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanoes, and fires. Edo was once destroyed by many large fires, such as the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657, which burned down more than half the city. Famine also occurred when crops failed, leaving many farmers in dire straits. Thus, the policy of isolation brought many benefits but also had significant limitations. The advantage was long-lasting peace. The Edo period was one of the rare times when Japan was free from war. The Tokugawa shogunate maintained order for over 200 years, a considerable achievement.

Furthermore, cultural development with stability and isolation also helped Japan avoid the fate of becoming a colony like many other Asian countries. But the downside was technological backwardness. While the West underwent the Industrial Revolution, Japan was almost stagnant in terms of technology. When Commodore Perry's fleet arrived, Japan realized how weak it was. In 1853, Commodore Perry's black ships arrived in the bay, demanding Japan open up trade. The Shogunate, with its weak military power, was forced to sign the Kanagawa Treaty, ending the policy of isolation. This event marked a significant turning point leading to the collapse of the Shogunate and the opening of the Meiji Restoration when Japan modernized rapidly to catch up with the West.